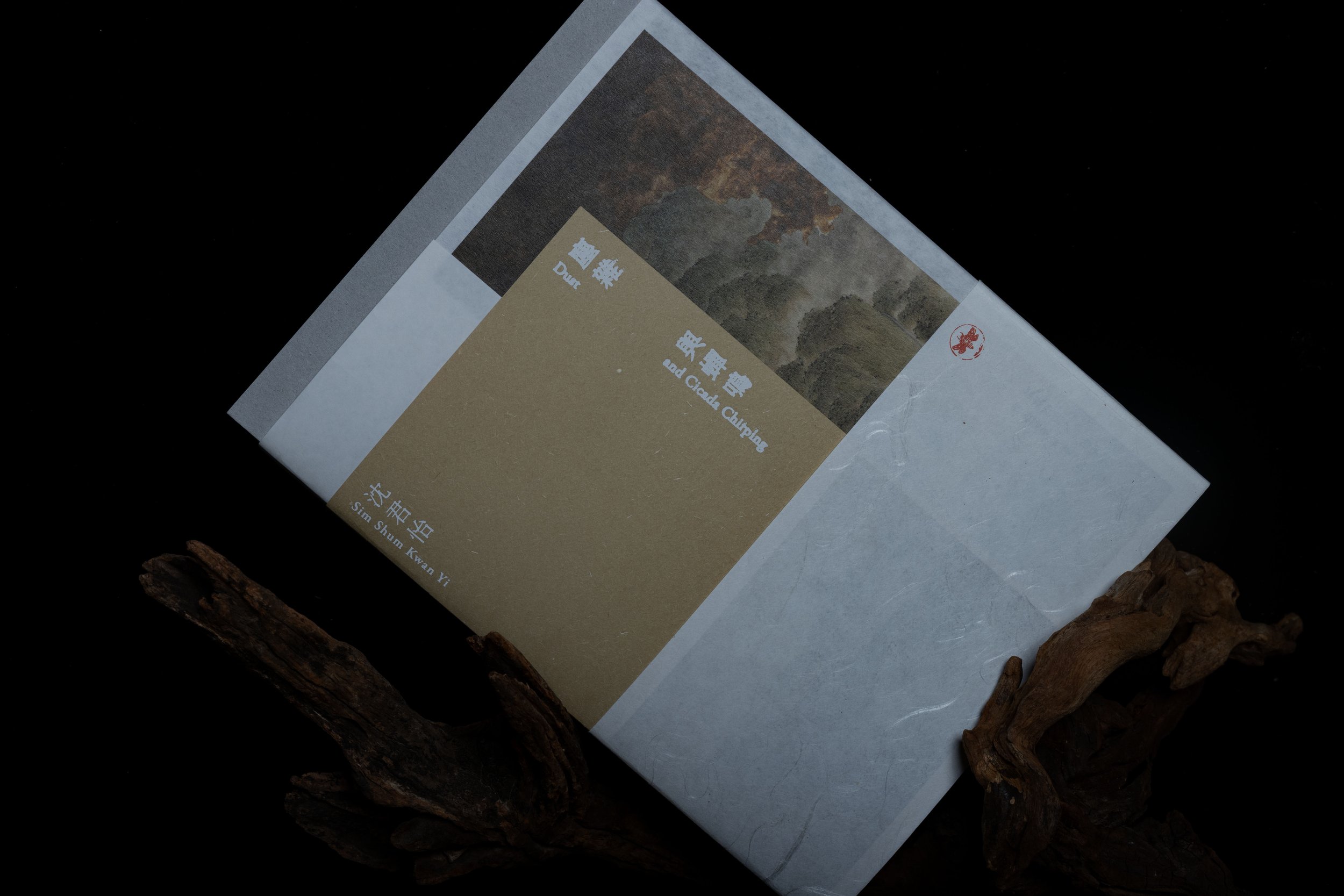

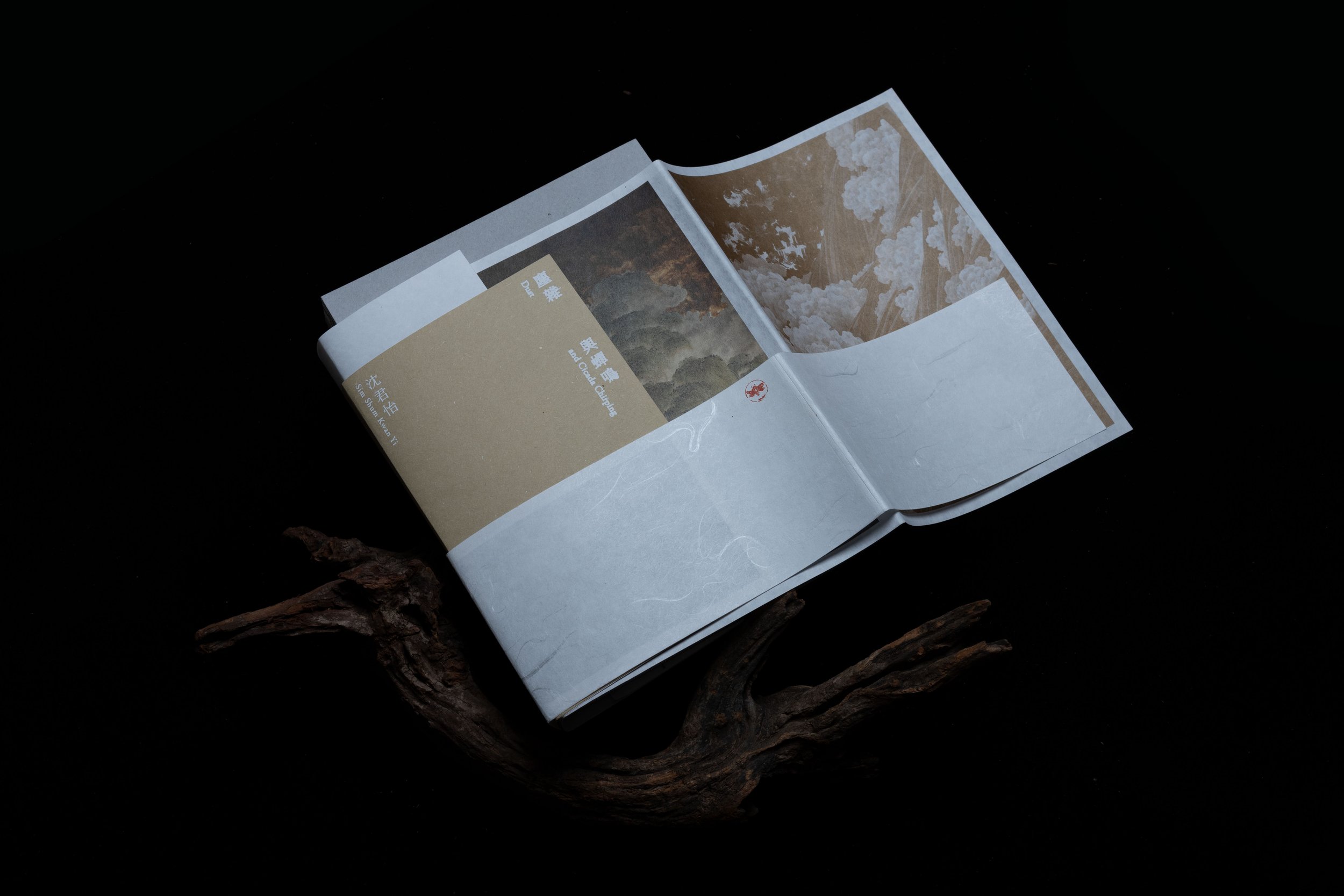

塵雜與蟬鳴 Dust and Cicada Chirping

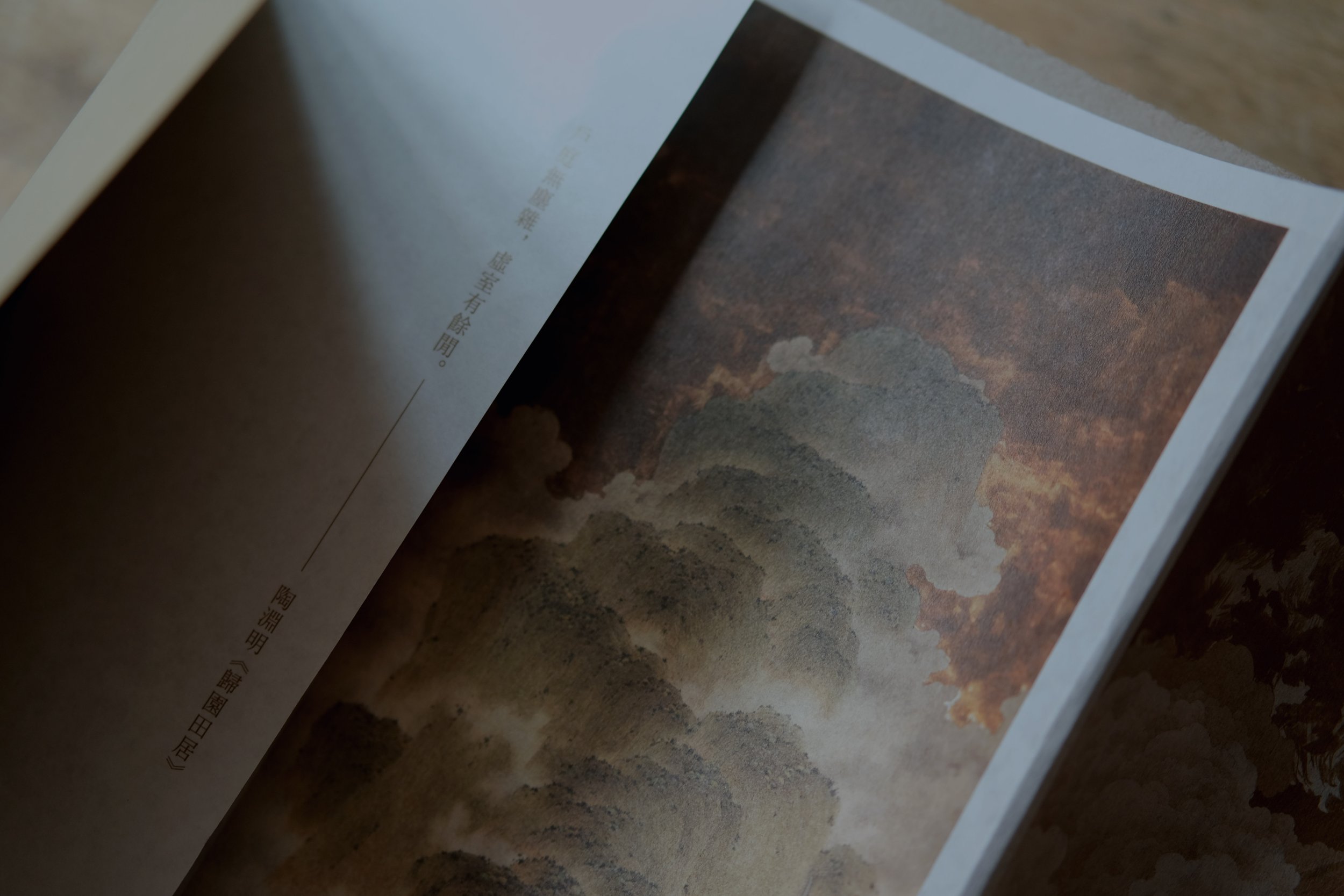

「塵雜」一詞解作塵俗雜事,源自於陶淵明《歸園田居.其一》中的一句「戶庭無塵雜,虛室有餘閒。」《塵雜與蟬嗚》意思是無法脫離塵俗雜事卻通過山與水喃喃自語;不善言辭卻希望以作品帶來安慰與共鳴。除了是次展覽中的作品外,本書更分別以城市遊者、不能承受的輕與石窟遊樂園紀錄了三個時期 (2019-2024) 的作品:由對自然的觀察到社會性的抒發。

The term "Dust" translates to "mundane and miscellaneous matters." It originated from a line in Tao Yuanming's poem Returning to the Fields, which goes, "At gate and courtyard—no murmur of the World's dust: In the empty rooms—leisure and deep stillness." The phrase "Dust and Cicada Chirping" conveys the idea of being unable to escape mundane and miscellaneous matters but finding solace and introspection through the murmurs of mountains and waters. Despite a lack of eloquence in words, I (the Cicada) hope to bring comfort and resonance through their artworks. In addition to the works featured in this exhibition, this book also documents my three periods (2019-2024) separately, capturing observations of nature and expressions of social issues through the chapters "City Wanderer," "The Unbearable Lightness," and "Landscape of Haven."

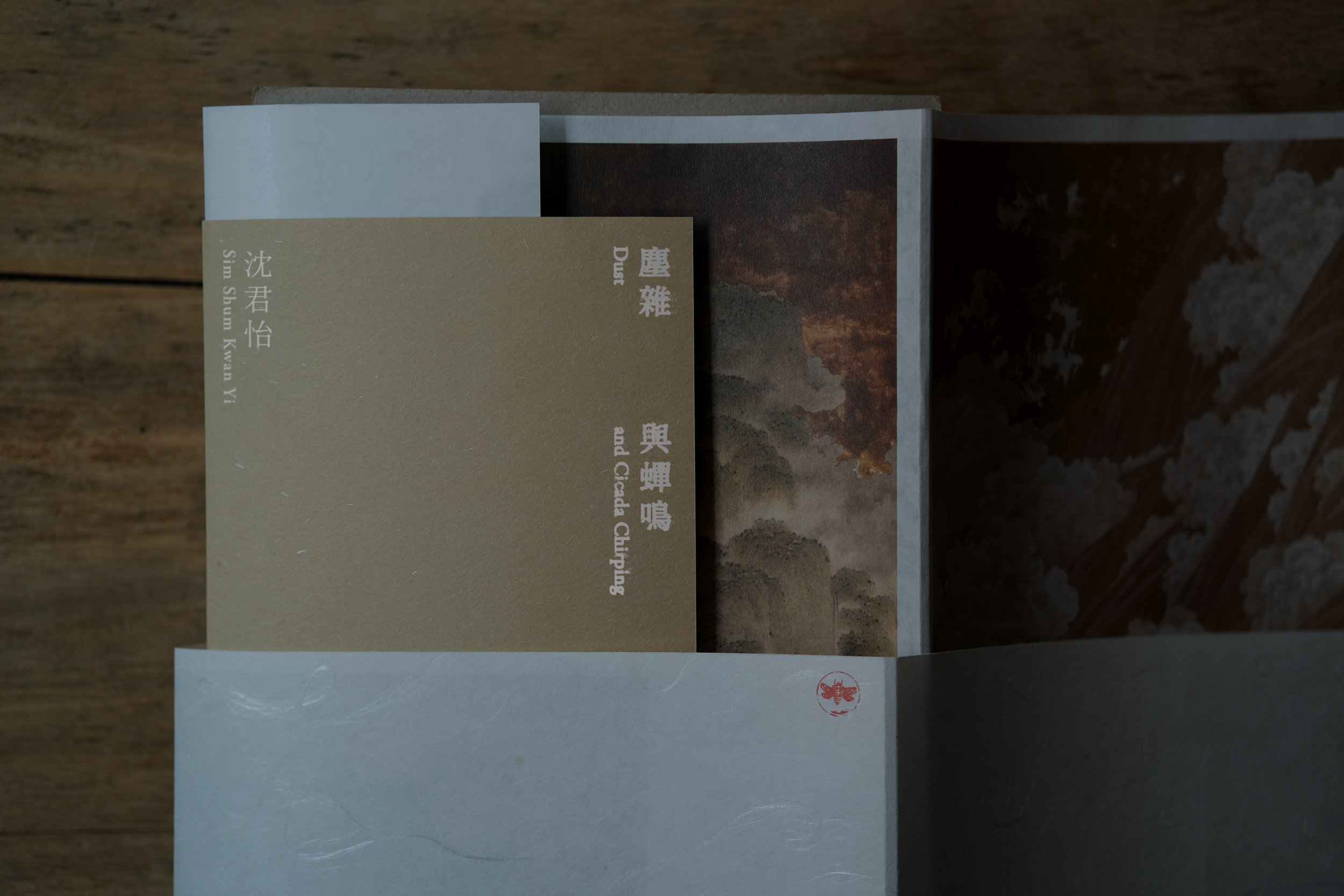

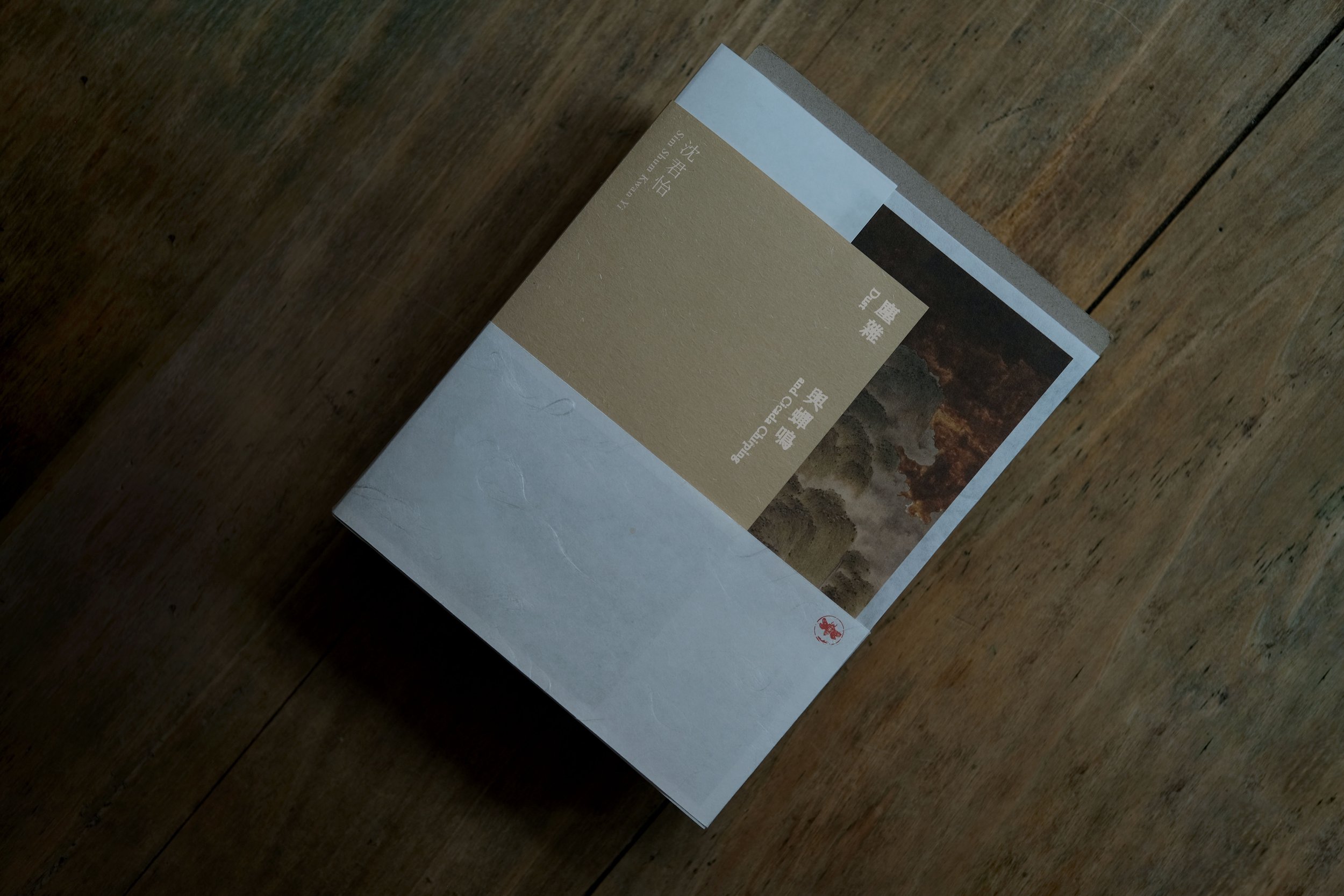

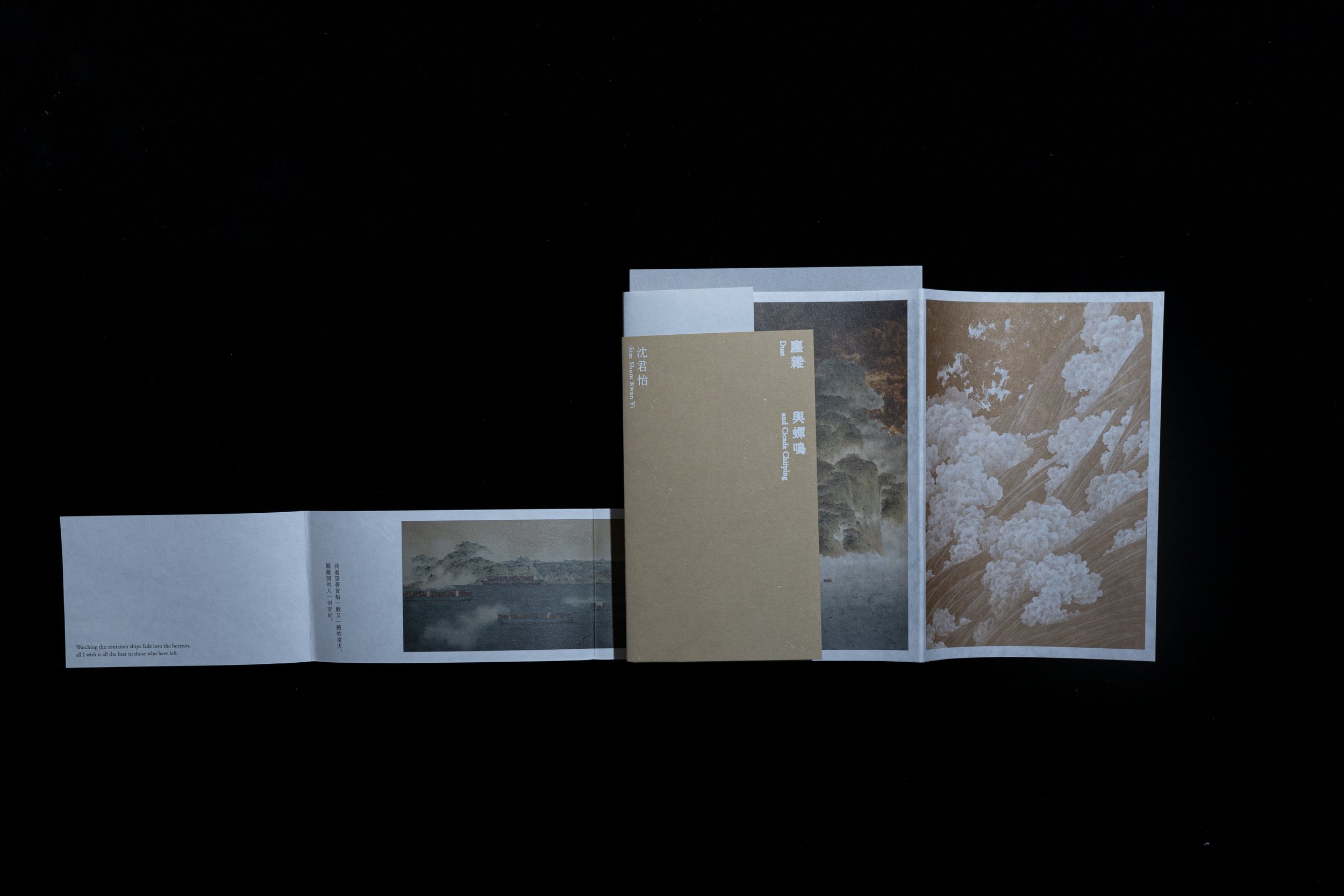

Foreword by: Henry Au-yeung 歐陽憲 and Dr Vivian Ting Wing Yan 丁穎茵博士

Published by: Shum Kwan Yi 沈君怡 and Grotto Fine Art Ltd. 嘉圖現代藝術

Year: 2024

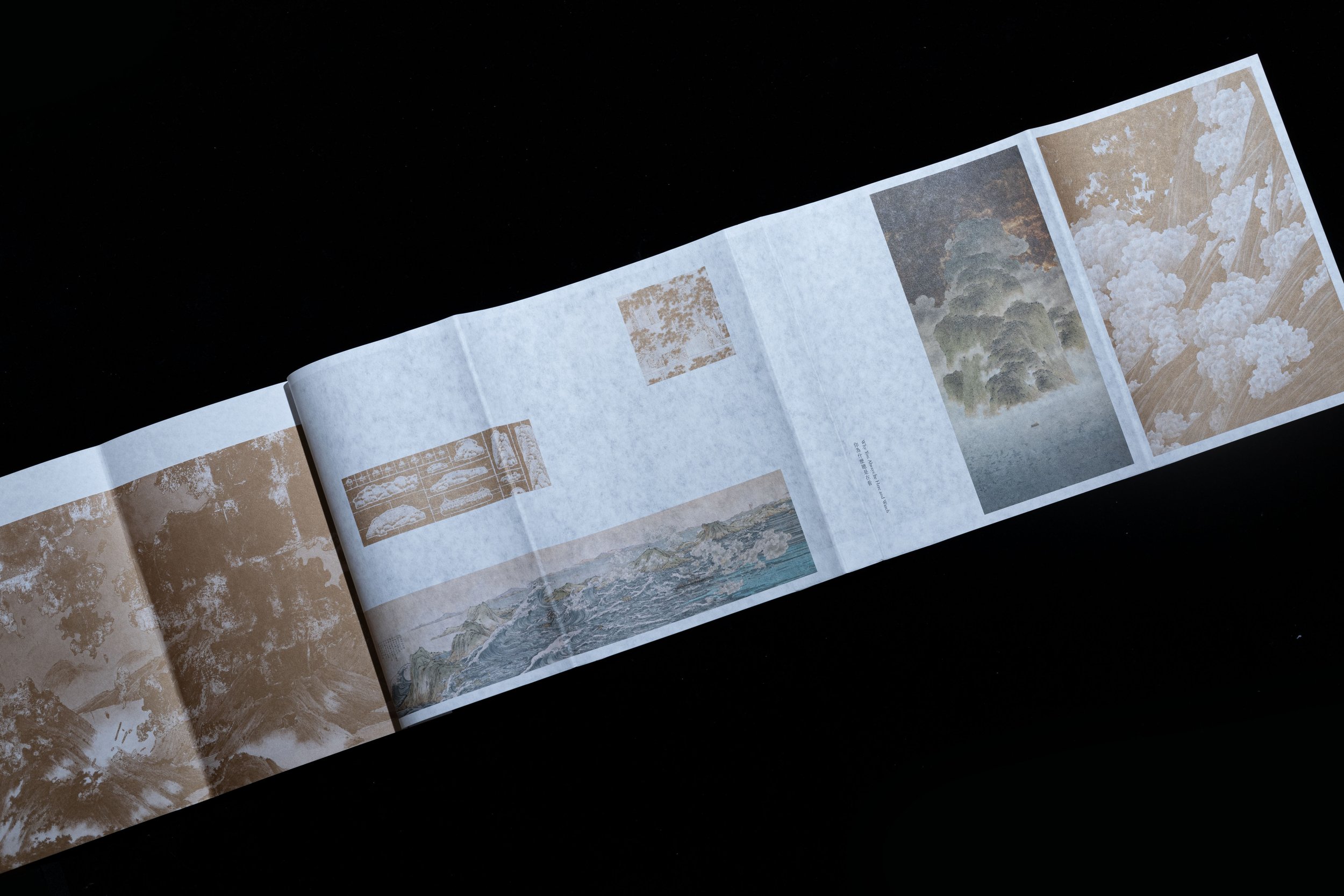

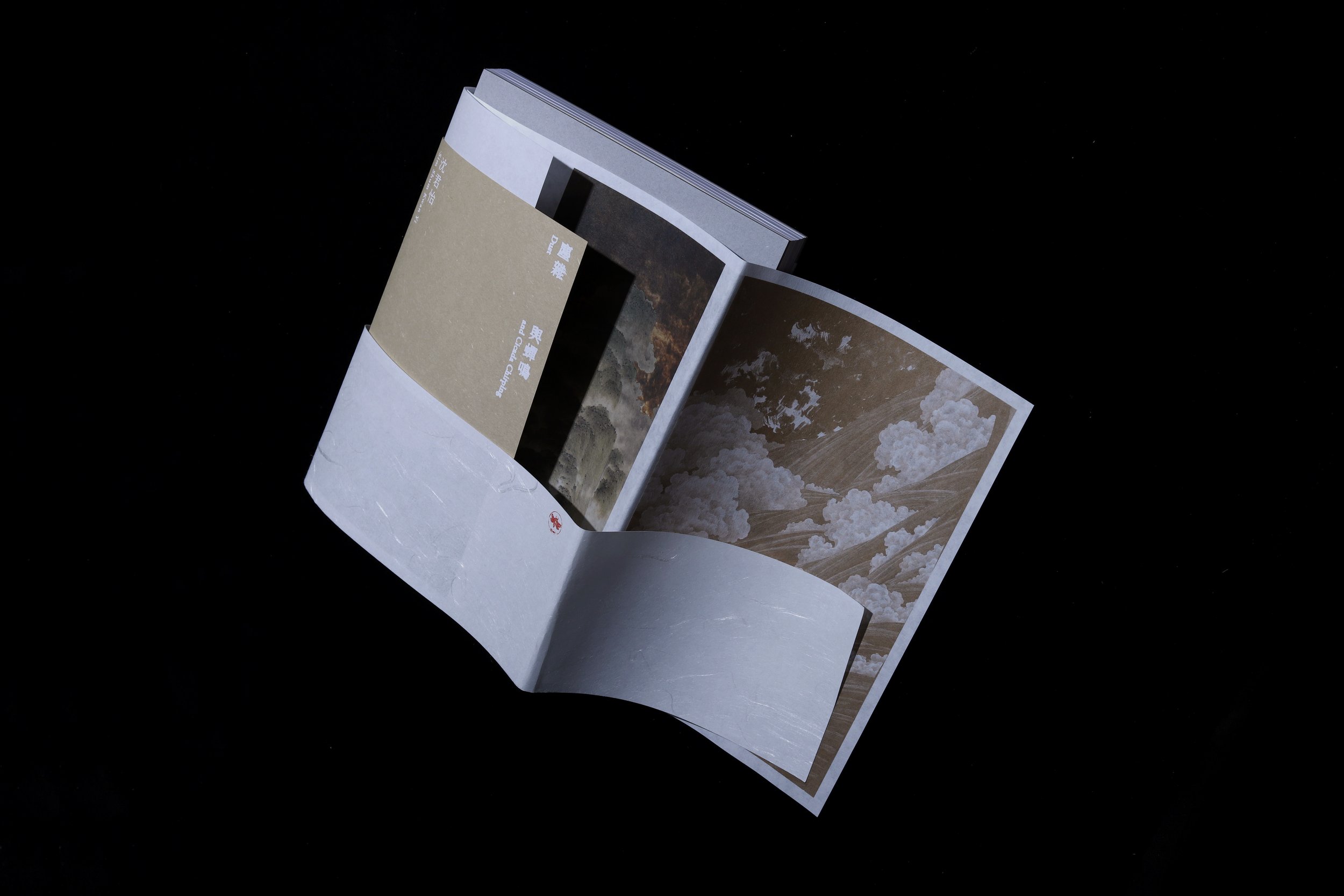

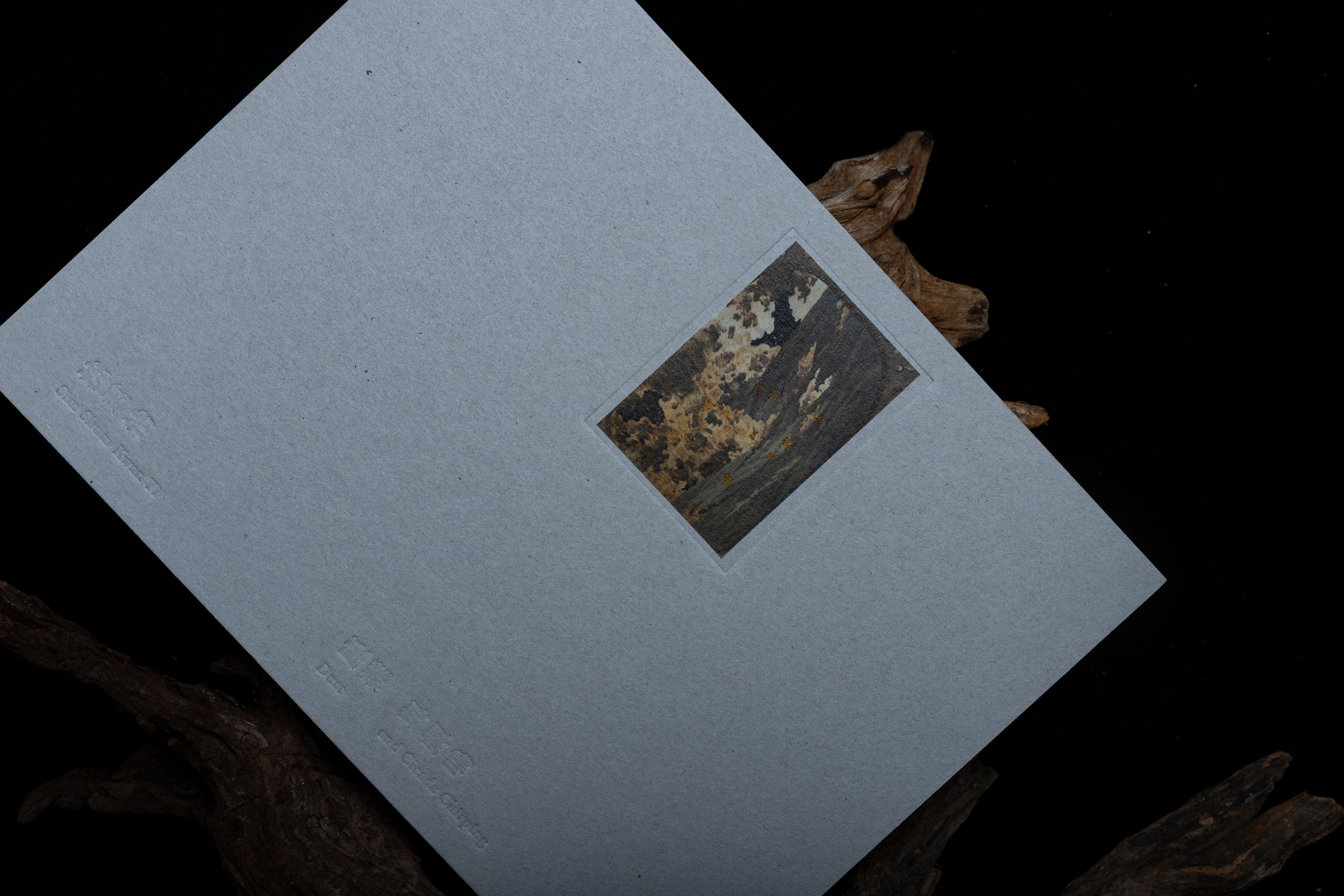

Format: 190 x 255 mm, 215 colour pages, Smythe binding

Design: for&st

Language: Chinese and English

Available on:

獵人書店 Hunter Bookstore

Wure area

shumkwanyi

Grotto Fine Art

Foreword

夢的行動 — 記沈君怡筆下的洞窟山水

Dreaming in Action — Notes on Sim Shum’s Cave Landscapes

丁穎茵博士 Dr Vivian Ting

「人類無可救贖地留在柏拉圖的洞穴裡,老習慣未改,依然在並非真實本身而僅是真實的影像中陶醉。」

‘Humankind lingers unregenerately in Plato's cave, still revelling, its age‑old habit, in mere images of the truth.'

-Susan Sontag

藏在洞窟的秘密 Hidden secrets of the caves

1900年,寄居敦煌石窟下寺的王圓籙道士帶人清理積沙,無意間發現了隱藏窟室,內裡埋滿了古舊經卷、文書、帛畫與刺繡織染等文物。自此這座名為藏經洞的秘室打開了陳封已久的敦煌記憶,讓人從壁畫看到佛的千姿萬態、衪的累世轉生、以至衪所居住的光明淨土。在幽暗石窟觀佛坐禪修行,原是通往解脫世間苦的法門。

In 1900, Wang Yuanlu, a sojourning Taoist monk staying at the Lower Temple in the Mogao Caves of Dunhuang, was leading a clean-up of the dilapidated caves when he inadvertently uncovered a hidden room, filled with ancient scriptures, documents, silk paintings and embroidered and dyed textiles. The secret room, now known as the Library Cave, unlocked distant memories of Dunhuang, revealing a series of murals showcasing the myriad forms and infinite incarnations of the Buddha, and the pure land of brightness that he inhabits. In meditation, practitioners sit in the dark caves and visualise the Buddha to cultivate concentration and inner peace as a fundamental way to achieve liberation from the world’s misery.

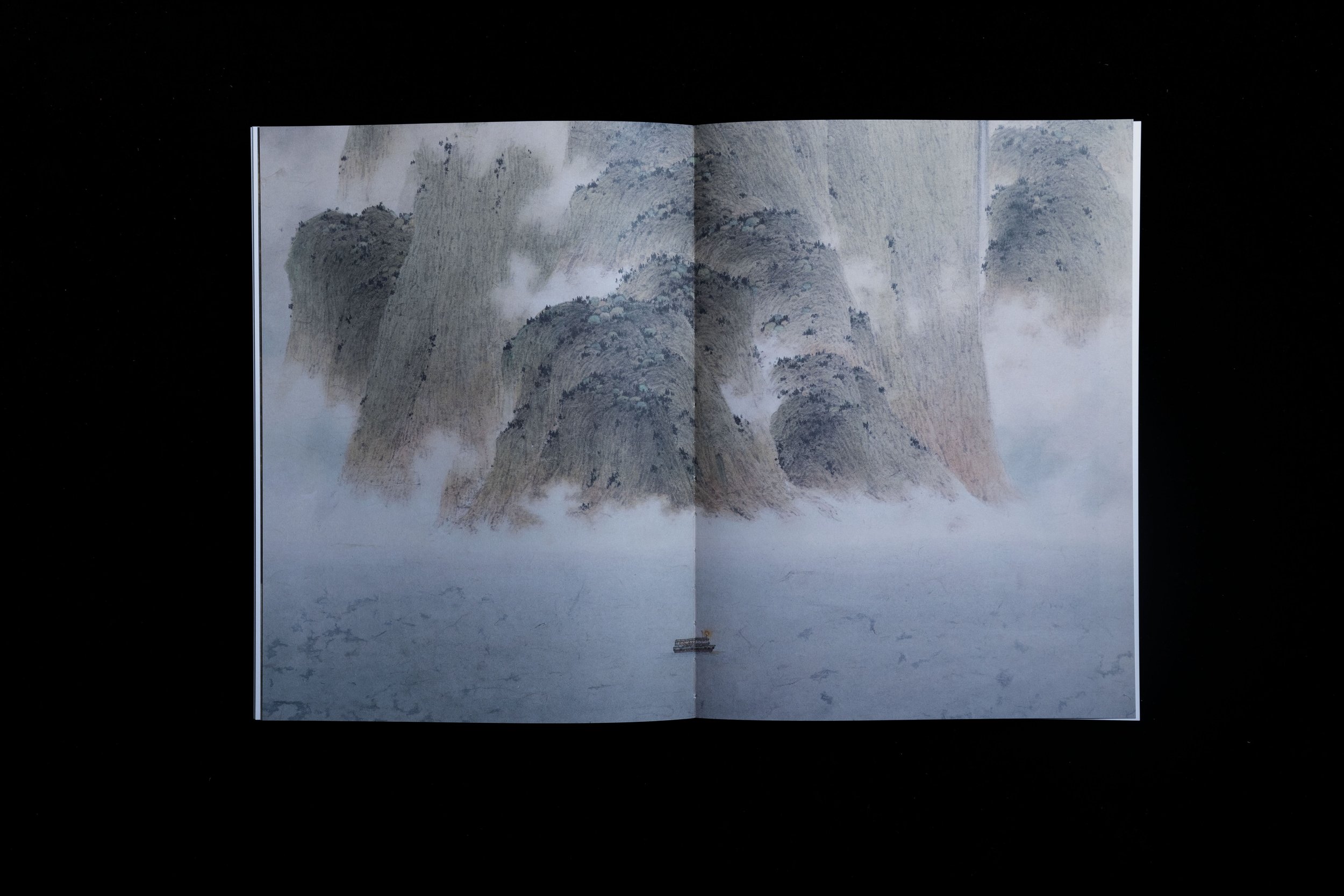

遙想千百年前樂尊和尚修建莫高窟的故事,藝術家沈君怡以時間與技藝一筆一劃的經營其繪畫樂園,邀請我們走入其抽離於現實的水墨洞穴。筆墨皴染的石窟沒有色彩、也不見人煙,卻看似洞內有洞一穴套一穴似的,藝術家的想像將往何處去﹖我們追隨著墨跡探奇,又將發掘什麼樣的秘密﹖

Reminiscing about how the Buddhist monk Yuezun carved out the earliest caves at Mogao more than a thousand years ago, artist Sim Shum creates her own niche of painting in meticulous gongbi style, inviting us to step inside the caves of ink far away from reality. Rendered with textural strokes and ink washes, the caves are absent of colours and figures, but seem to go on in layer after layer. Where does the artist’s imagination go? What secrets will we discover if we continue exploring her ink works?

在想像的洞窟裡,看得見什麼﹖What do we see in these imaginary caves?

且看作品〈第一窟〉,觀眾正置身暗無天日的洞穴,眼前景象倒似從大小不一的電腦螢幕轉譯而來,顯得無邊際、無方向、無地平線、亦失去空間深淺遠近的感知。桀驁不馴的自然竟也乖巧起來 — 一株株秀樹雖然參差有致,但清一色的整整齊齊挺直枝幹排列成陣﹔一顆顆石頭玲瓏巧峭的裝點著方格,卻盡失駘蕩層纍的氣勢﹔沙磧緩坡蹲踞如孤島,就連苔點纍纍的山巒也瑟縮成補釘似的。舉目遠望,洞外天色陰晴不定,遠方一艘輪船滑過波瀾不驚的汪洋。從另一洞口看出去,水平線驟升,而那閃亮亮的發光體又守在附近蠢蠢欲動。天曉得,洞外世界會否更荒誕、更孤寂、更叫人不知所措﹖

In Cave No. 1, the viewers are thrown into the darkness of the cave, where the scene transforms into an assemblage of computer screens of different sizes, appearing boundless, directionless and horizonless with its lack of spatial depth. Even the unruly wilderness has been brought to heel — straight trees of varying heights are neatly lined up; rounded stones fill in the grids decoratively but the majestic allure of layered mountains has completely disappeared; beaches and gentle slopes lay quietly as isolated islands, and even the mountain ranges covered with ink dots are reduced to patches of fabric. Far off in the distance, outside the cave, there is a ship sailing across a calm sea under uncertain skies. Viewed from another entrance, the horizon rises suddenly when a luminous object guiding nearby is eager to take action. Who knows if the world outside the cave is even more absurd, lonely and overwhelming?

這就是沈君怡筆下工整得離奇的「繪畫空間」。畫家捨棄了透視規律及幾何學造型要訣,將山水景觀壓縮成二維平面,看來倒像自然生態的規劃圖。觀眾找不到進入繪畫空間的視點,也難以判斷自身與畫作題材之間的關係。我們身處於什麼位置觀看洞窟風光﹖那是穴居者的視線、局外人的角度、還是採納藝術家的全知觀點﹖再三細看畫面的形狀與圖像,我們試圖理解洞窟世界運作的邏輯,卻始終不得要領。為什麼眼前所見山非山、石頭長得不像話﹖樹木為何或呆立、或橫躺、甚或上下顛倒﹖唯一打破穴窟的方塊佈局,是那驟眼看來滔滔東去、實則蜿蜒曲折衍溢四方的水流。豈料暗中一只手硬生生抓著一棵樹,另一只手緊隨其後勢似搶奪這算不上珍奇的自然資源。莫非這是命運之手﹖抑或是欲望驅策的土地開發之手﹖

This is Sim Shum’s ‘painting space’, where objects have a bizarrely neat arrangement. Her works resemble ecological planning sketches, as she forsakes perspective and geometry and instead compresses the composition into a two-dimensional plane. Therefore, it is difficult for the viewer to find a point of view to take in the space of painting and to determine their relationship with the subject matter. From which perspective are we observing the cave? Is it from the perspective of a caveman or an outsider, or do we adopt the artist’s omniscient viewpoint? We try to understand the logic of the world inside the cave by looking at Shum’s forms and images again, yet we still have not the slightest clue. Why don’t the mountains and rocks look as they should? Why do the trees dawdle, or lie down, or even be placed upside down? The only thing that breaks the grid composition is a winding river that seems at first glance to flow to the east but actually goes in all directions. All of a sudden, a hand emerges and holds on to a tree, and another hand reaches from behind to snatch the tree, a not-too-valuable natural resource. Could these be the hands of fate, or are they just the hands of the desire-driven land developers?

我們游目四顧,想要進入畫作所描述的想像世界理解其邏輯。但作品拒絕吐露箇中奧妙,迫著我們將眼睛停留在畫作的表面。過去水墨山水作品可視為可觀、可遊、可居的萬物舞台,藉由山的纍纍堆疊、水的淼淼漫漫、煙雲的氤氤氳氳,讓人穿透繪畫的表面,看到自然萬象背後生生不息的力量。但沈君怡選擇以單純得近乎天真的方式重構山水佈局,空間割切成或方或圓的面塊,萬物又轉譯成看似毫無關連的圖像符號,誘發多重的觀看經驗—假設、推論、演繹、否定,又再探尋畫面世界的所以然。與其說畫家描畫的是洞穴秘室的想像,倒不如說她向我們展現了其想像世界的壁畫。即使看到畫作暗示的穴窟出口,我們依然無可逃遁。又或者說,我們遊移在畫作的表面,卻不知就裡,只得直視圖像的詭奇,並且在不斷調整觀看方式之間,墮入了想像的洞窟。

We look around trying to enter the imaginary world of the painting and work out its logic, but the artwork refuses to reveal any secrets, forcing our eyes to stay on the surface. In the past, Chinese landscape painting was viewed as a natural realm that the viewer could appreciate, traverse and inhabit with their eyes. With the mountains stacked one on top of another, long rivers snaking through the landscape and the curling smoke of mist and clouds, the viewer can penetrate the surface and see the perpetually thriving force behind all things in nature. Nevertheless, Sim Shum chooses to rearrange the landscape composition with an approach that is simple and almost naive. Space is divided into square or rounded planes, and all natural things are translated into seemingly irrelevant symbols, offering multiple viewing experiences — to make hypotheses, inferences and deductions, reject them and then continue exploring the reasons why the world of her subject works in a particular way. Not that the artist paints the hidden caves in her imagination so much as she presents to the viewer the murals of her imaginary world. Even if we can see the entrances of the caves implied in her works, we still have nowhere to go. Or in other words, our eyes are made to wander over the painting’s surface without knowing what is exactly going on. All we can do is to gaze towards the strangely arranged objects while consistently adjusting the way we look at it, falling into the cave of her imagination.

穴居世界,看得透,不﹖Do we understand the world of cavemen?

記得柏拉圖的一則寓言,述說某洞窟住著一群頭頸與手腳為鎖鏈所拘限、無法扭頭向後看的野蠻人。他們天天盯著石壁,誤以為洞口投射入內的陰影就是世界的模樣,從未想過只要踏出穴窟就可以親身體驗真實的世界。千百年後,Susan Sontag引用柏拉圖的寓言,直指我們就像穴居者,而拘禁我們的卻是十九、二十世紀引以為傲的攝影技術。她歸咎照片的記錄比肉眼所見的真實世界更清晰鮮明,令人慣於以觀看取代親身體驗,反倒失去了穿透表象、理解身邊事物的判斷力。

In one of Plato’s allegories, he describes a group of people who have had their necks and limbs chained to the wall of a cave all their lives and cannot turn their heads around. They are forced to face the wall and watch the shadows projected on it from objects passing by the entrance of the cave, mistaking them for reality. Never have they thought they could experience the real world by just leaving. Thousands of years later, Susan Sontag uses the concept of Plato’s cave to point out we are similar to those cavemen, and what has imprisoned us is the technology of photography that has made people proud in the 19th and 20th centuries. She blames the fact that photographic records are clearer and more vivid than the real world we see with our own eyes. As a result, we are too used to perceiving things by seeing them instead of experiencing them, thus losing the judgement to see through the surface and comprehend things around us.

不無諷刺的是,今天我們活得比過往更像穴居人。智能手機、桌上電腦、電視、電競遊戲機填滿了生活,我們與外界的聯繫大可透過大小螢幕通通辦妥,萬象世界也一再壓縮成各式各樣的圖像—攝影圖片、電腦合成影像、AI生成繪畫等,讓人身陷美學幻覺再拼湊不出世間的「真實」。

Ironically, we live even more like a caveman compared to the past. Our lives have become so reliant on technologies such as smartphones, computers, televisions and esport games. While we can simply connect with the outside world through screens, the world we live in is compressed into all kinds of images — photographs, synthetic images and AI-generated paintings, lulling us into the aesthetic illusion that we can no longer conjure up the world’s ‘reality’.

顯然,沈君怡的繪畫誘發了我們對當代穴居生活的聯想。創作人明言只想築構自己的洞窟、遠離現實的喧囂。可是,她與我們身處在同一世代,也生活在相同的歷史、文化與社會情境。作品對於洞窟的想像,說明畫家有意無意間,早已將當代人的生活處境與視覺文化融入其中。

Sim Shum’s paintings are evidently evocative of cave life in a contemporary sense. She wants nothing more than to build her own caves and tuck away from the bustle of the real world. However, she is in the same generation as us, and we live in the same historical, cultural and social environment. Her portrayal of the imaginary caves incorporates, either by accident or coincidence, elements from the lifestyle and visual cultures of her contemporaries.

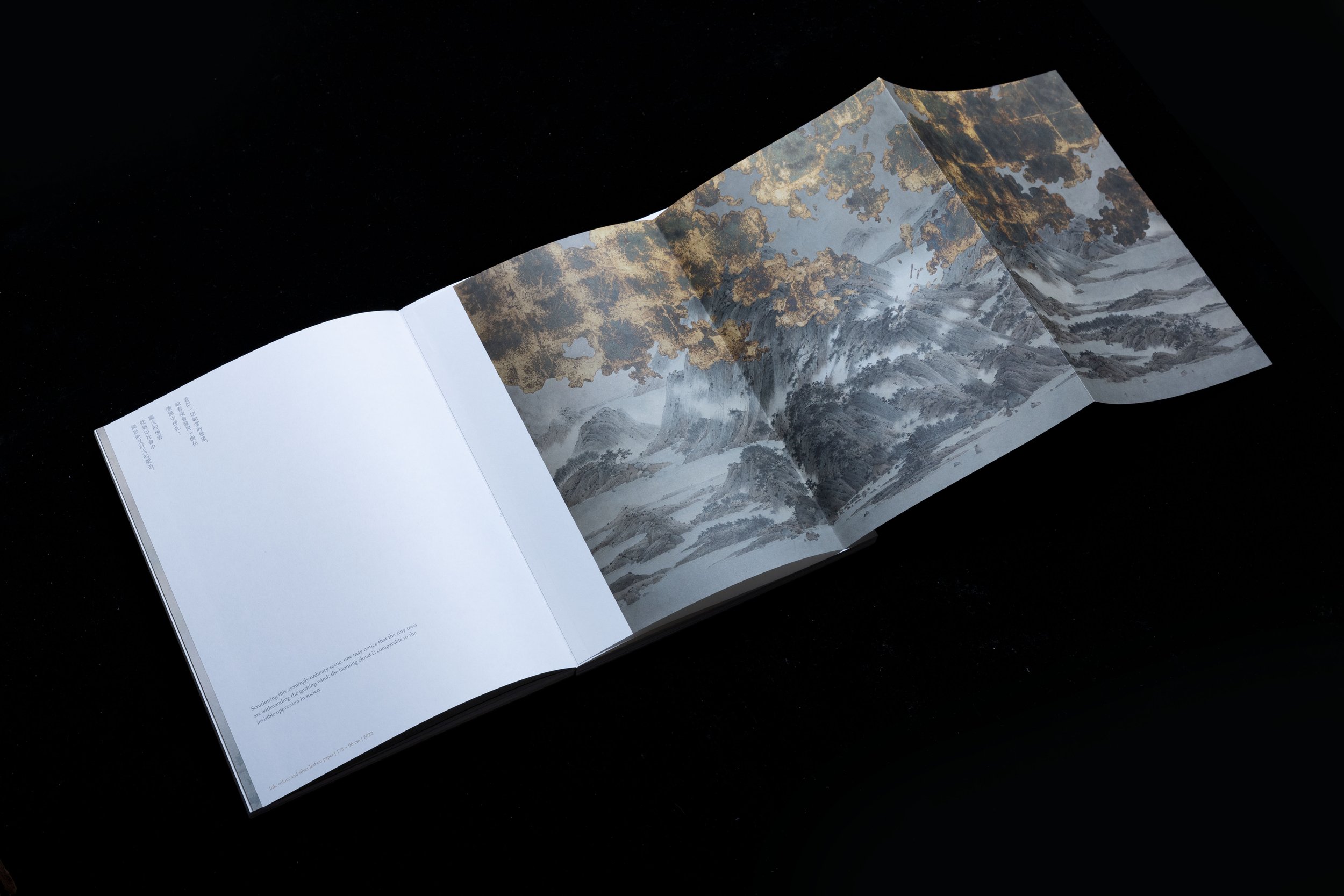

如作品〈第二窟〉、〈第三窟〉,畫家開出一個又一個洞口,就像庭園借景似的,向我們展現了千奇百怪的山石田、樹木陣與流水路。然而,我們依然無法深究洞窟空間的邏輯—大小洞口如何相互連接、又通往何處﹖洞口所見的風景又表明什麼樣的洞中洞結構﹖在這洞窟世界,我們看到的是景象各有不同的畫面,但總說不清畫面之間有沒有關連,甚至無法判別時間於其間推演的痕跡。水墨畫創造的異想世界既表現了藝術家沈君怡面對時代的感懷,也指向了她與觀眾共同擁有的視覺經驗—電腦視窗、社交媒體貼文與分頁瀏覽器打開出了浮華萬象的諸般色相。一頁頁圖像與訊息看似明明白白,但它們如何建構我們所理解的世界﹖種種資訊勾連著什麼樣的社會文化脈絡、又涉及誰的價值觀與意義﹖

In Cave No. 2 and Cave No. 3, the artist cuts out openings in the caves, one after another, to show viewers a strange arrangement of mountains, rocks, fields, tree clusters and waterways, seemingly inspired by the concept of borrowed scenery in Japanese garden design. Still, we can’t figure out the logic in the space of the caves — how are the caves’ entrances connected to each other, and where do they lead? What does the scenery outside reveal about the cave structure? While we can see different planes of images within this world of caves, we cannot know for sure if there are connections between these planes, let alone how the planes have evolved in time. The alternative world that the artist opens up in her ink works is not only an aesthetic expression of her feelings towards the time we are living in, but also a representation of the visual experience she and the viewers share — computer screens, social media posts and browser tabs rivet our gaze towards the ostentation and spectacle of this mundane world. The images and texts appear to be easily accessible, but how do they build up the world as we understand it? How is all this information grounded in social and cultural contexts, related to values and meanings?

無論身處洞窟世界、抑或現實生活,我們的確身陷真真假假的迷障。

Indeed, we are living in a state of bewilderment in which the distinction between truth and falsehood is obscure, whether in the caves or in reality.

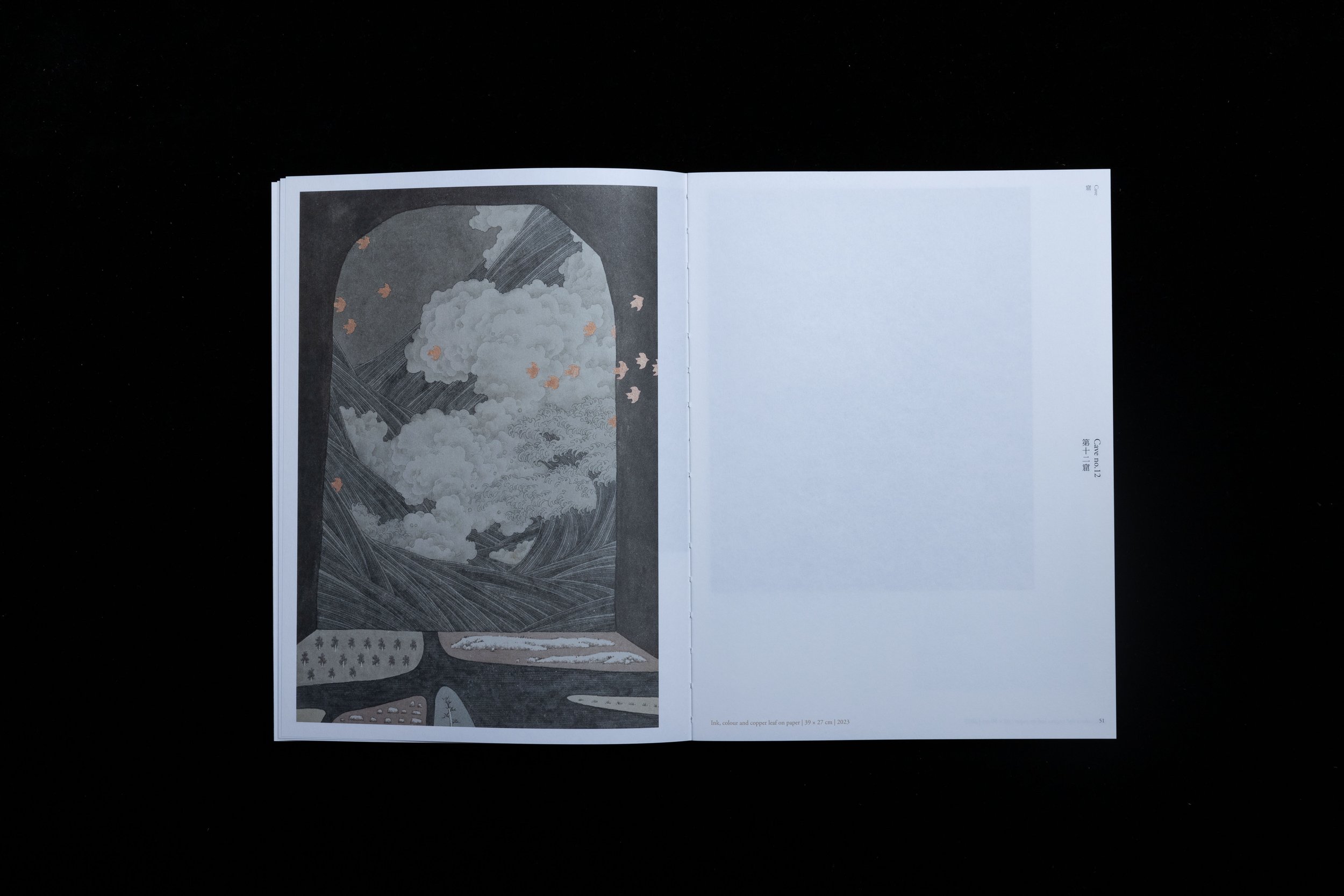

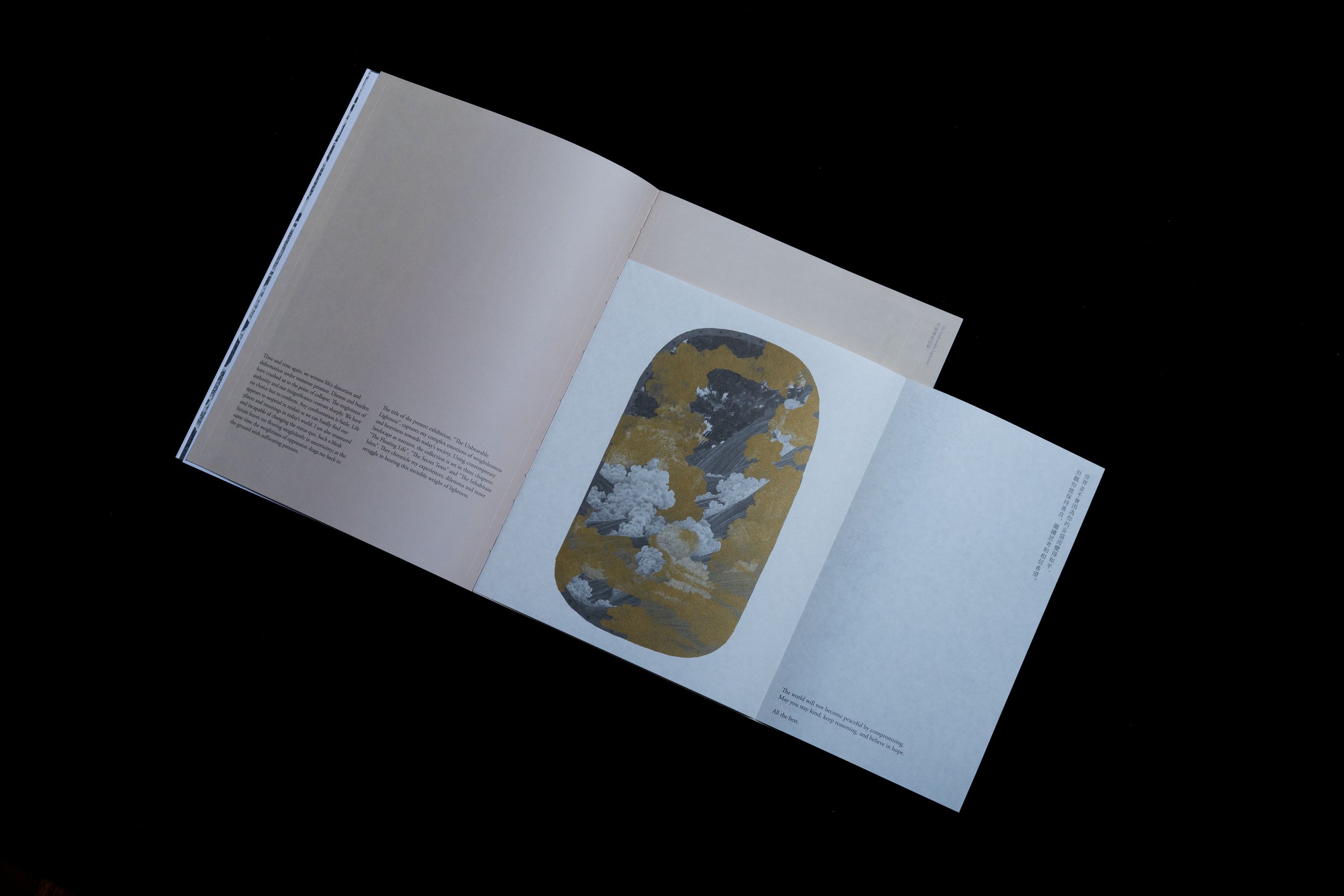

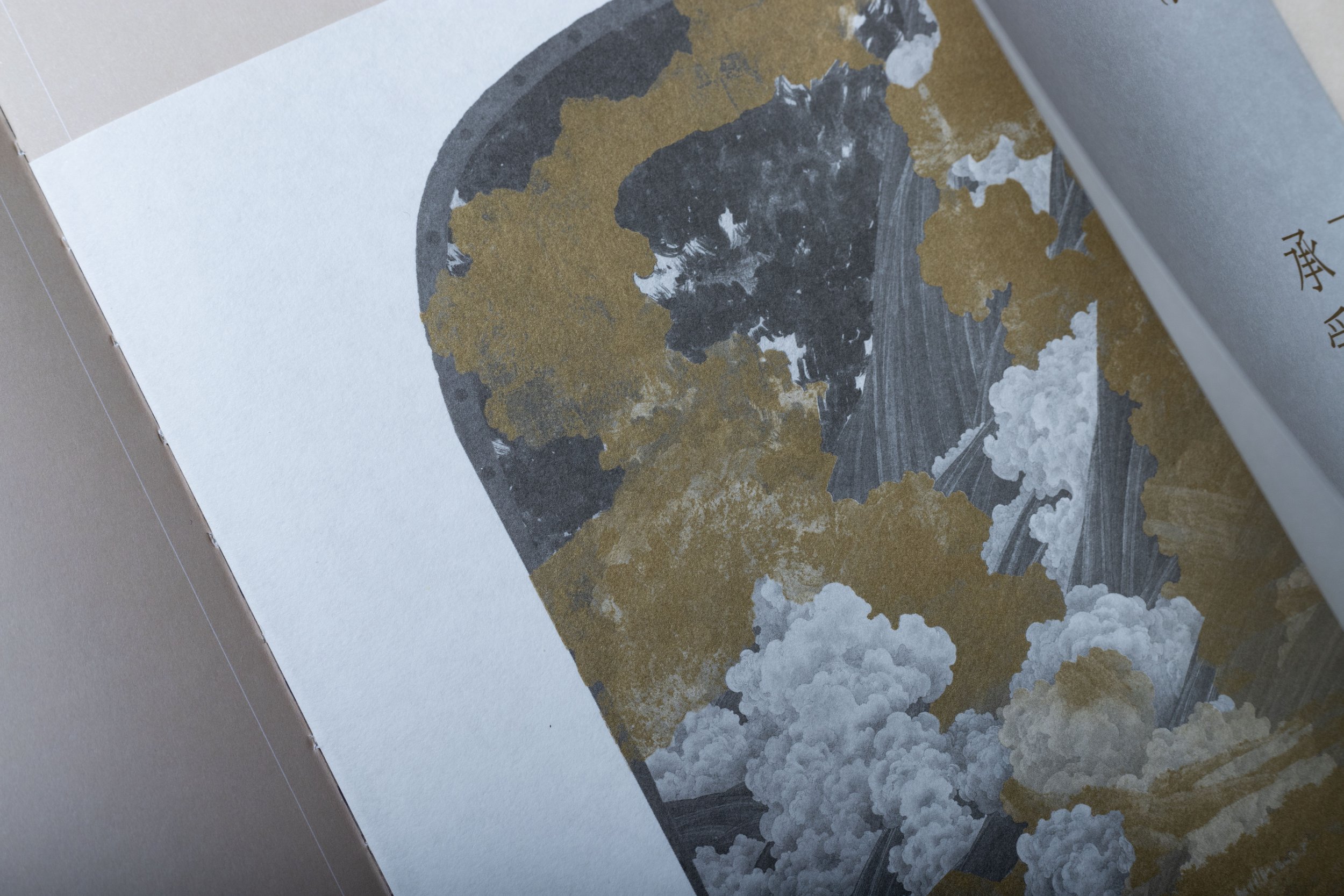

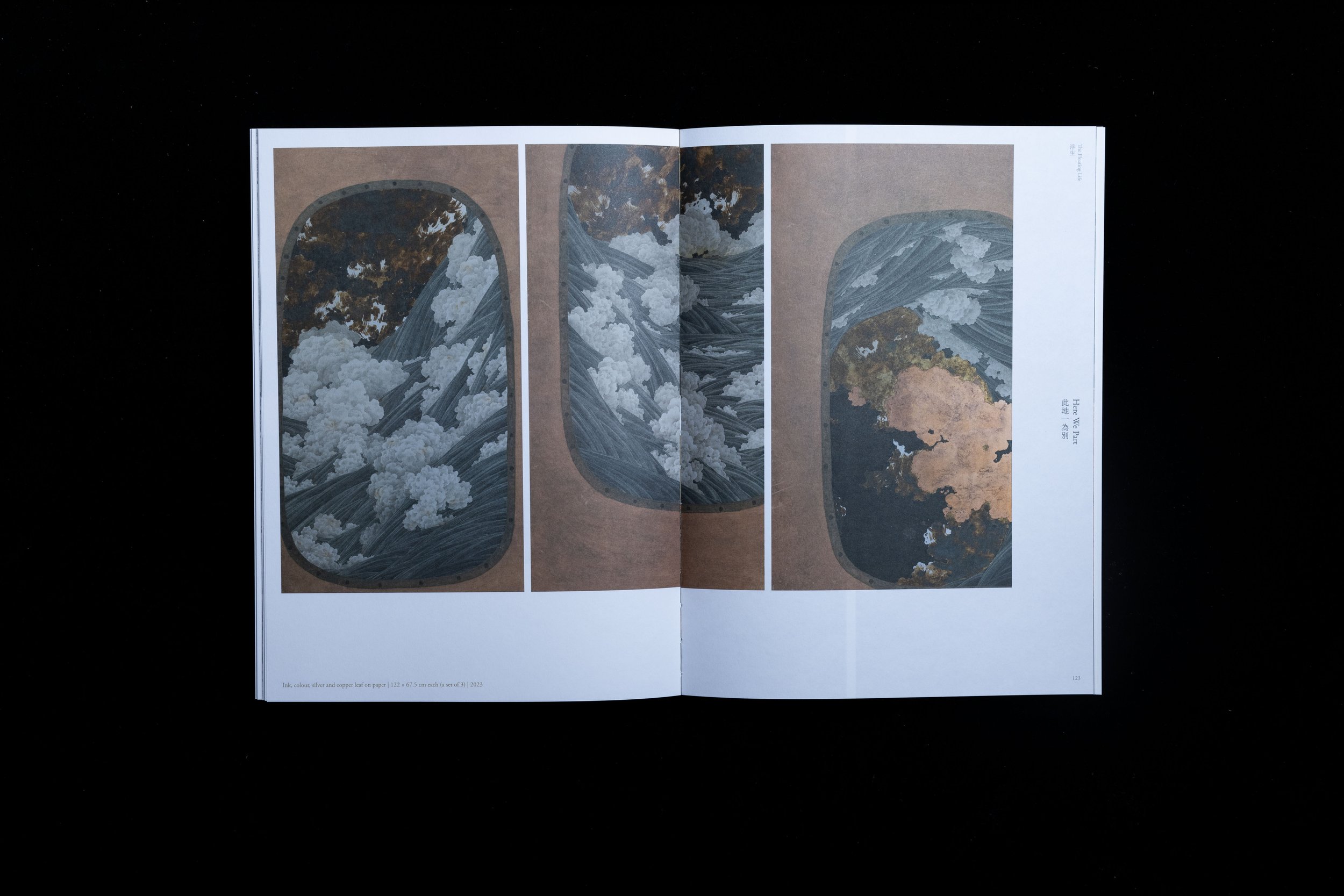

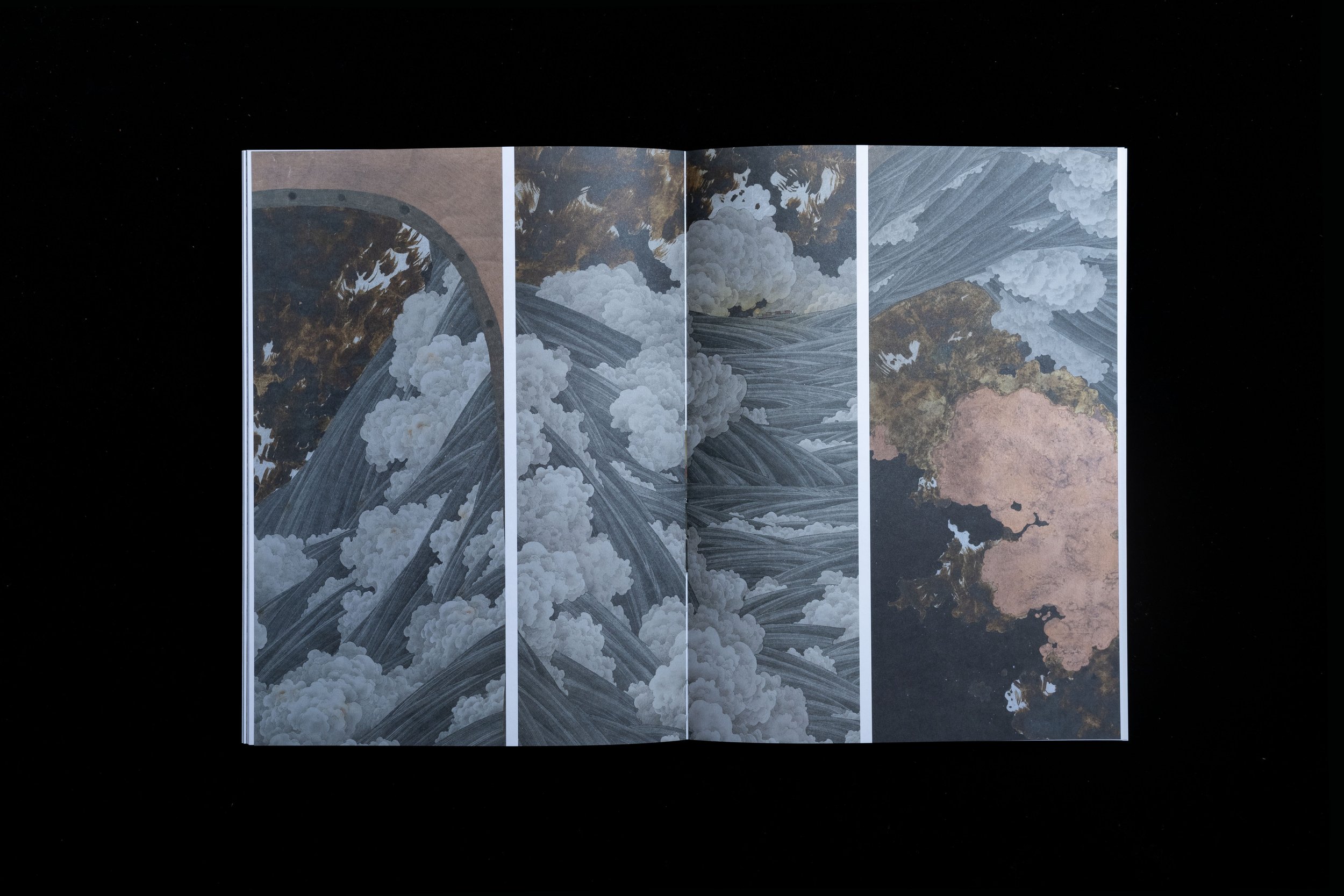

在〈第十五窟〉,藝術家以深淺不一的洞門暗示內外空間的區間,但氣根盤繞的「洞口」看似另一重洞壁,又讓人懷疑這不過是真作假時假亦真的繪畫手段。即使〈第十二窟〉以半圓拱門似的洞門架起立體空間,但洞口翻天巨浪卻顯然與洞內世界截然二分,而金光燦然的飛鳥竟然像拼貼似的黏附著畫面,再次抵消了空間的幻覺。或許我們窺見的,僅僅是洞窟想像微不足道的片面。這一系列畫作所展示的,還有許多觀眾尚未看得清楚、未曾領略的,又或藝術家故意魅惑眼睛的部分。虛虛實實似是而非之間,作品觸發觀眾無窮的聯想,也不斷修正我們觀看的方式,追問著我們看什麼、如何看、又如何理解眼前看到的「世界」。

In Cave No. 15, the artist uses varying tones to depict the cave’s entrances to imply a separation between interior and exterior space. However, the cave’s entrances, where the long, tangled aerial roots hang, look like the walls of the cave, leading the viewer, in a time when the true is indistinguishable from the false, to wonder if this is just a painting on the walls. Although the huge arch at the entrance in Cave No. 12 delineates the three-dimensional space of the composition, the soaring waves outside are worlds away from the inside of the cave. The shiny golden birds, resembling a paper collage, also stamp out the illusion of spaciousness. Perhaps what we see is merely a lopsided representation of the imaginary cave. In this series of paintings, there are still parts the viewers have not seen clearly and grasped, or those are the parts with which the artist intends to mesmerise the viewers. By creating a world of enigmas blurring the line between dreams and reality, the artist’s works stimulate endless imagination in the viewer's mind and constantly amend our perception, raising further questions about what we see and how we see it, and how we interpret this ‘world’ before our eyes.

夢的築建與解構 Construction and deconstruction of dreams

儘管這世代幾乎被五花八門的影像淹沒,我們卻比過去更需要繪畫。因為影像來得太快太易,我們未曾看得明白,其他花花綠綠的又紛沓而來。可是,繪畫卻要求觀眾停下來,從看得見的構圖、題材以至其筆觸用色等,感受畫中物的質地、溫度、情緒,以致其不甚看得見的脾性與氛圍。觀看繪畫的經驗關乎眼睛如何接收視覺資訊,也在乎腦神經如何連接記憶庫存的經驗,繼而轉化為感官的觸動、情緒的迴響以及智性的分析。

Although this generation is already inundated with all kinds of images, we need paintings more than we did in the past. Images come and go so quickly that before we can digest what we see, more lively, stimulating images have already shown up. Meanwhile, paintings require viewers to stop and examine the composition, subject matter, techniques, and colours, through which they can experience the texture, temperature, mood and even the less visible elements such as temperament and atmosphere. Apart from receiving visual information with our eyes, the experience of looking at paintings is also related to how nerves retrieve memories of the past and then transform our vision into sensory perception, emotional resonance and rational analysis.

John Berger曾說﹕「繪畫變得像圖式似的藝術。畫家的工作不必再現或模擬已經存在的東西,而是總結各種經驗。」是次展覽,沈君怡就以〈窟〉與〈景觀模型〉兩組畫作,總結了她身處穴居世代的城巿生活經驗。

John Berger once said, ‘Painting became a schematic art. The painter’s task was no longer to represent or imitate what existed: it was to summarise experience.’ In this exhibition, with her series Cave and Landscape Model Accessories, Sim Shum summarises her experiences of urban life as a member of the ‘cave-dwelling’ generation.

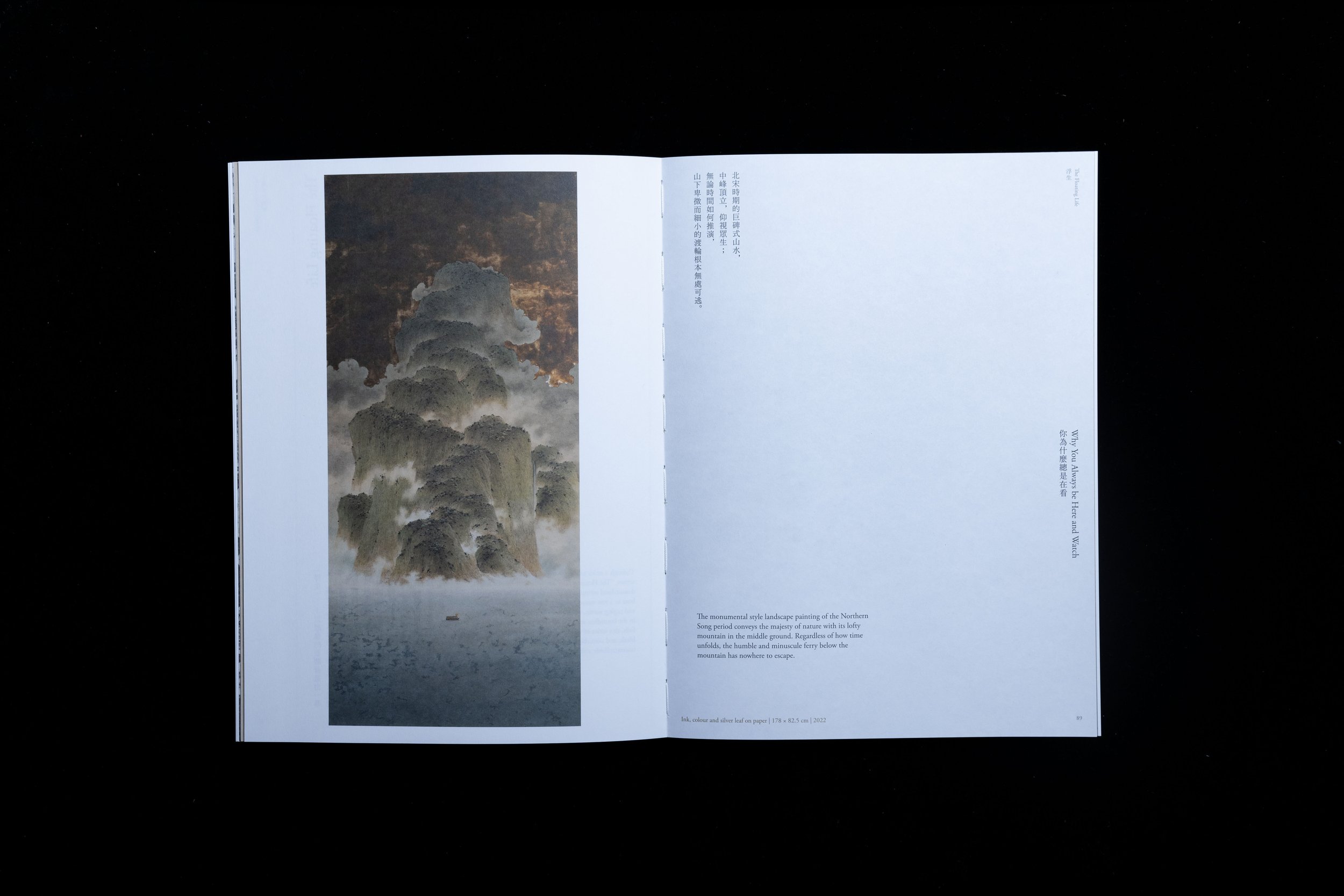

在香港這座密不透風的石屎森林,從一個狹小盒子移到另一個牙籤空間,再擠進又一個勉強容身的單位,就是我們生活的日常。人尚且如此,樹木更不得不委曲求全。它們要麼困在根莖難以舒展的行人路、要麼依附於雨水也無法滲透的石屎牆,要麼砍去枝幹硬塞進細小花盆。不消說講求便捷、效率與利益的城市,山必須移平,好將石材泥土當作建築材料,拿去修路築橋與填海。

In the concrete jungle of Hong Kong, moving from a bed cubicle to a tiny room to a barely liveable apartment unit is an everyday reality for many people. Even people are put in such a dire situation, never mind the trees that are resigned to growing in small spaces. They are found growing either in paved areas where their roots cannot spread or on cement walls that are impermeable to rainwater. Some of them have their branches and stubs chopped off and are placed in narrow planters. In this city where convenience, efficiency and benefits are the highest priority, hills have to be flattened to provide rocks and soil for road repair, bridge construction and land reclamation.

藝術家總結城市生活的感覺,其作品的構圖佈局總帶著幾分現代建築的機械理性,而落筆又不無憐惜的將巨輪、林木與山石畫得纖秀如掌中珍玩。天然的山水圖像與人造的現代設施模型均顯得筆觸柔和敏銳、線條翩然細膩,彷彿以水墨洗滌塵埃,創造出沈氏樂園的恬淡靜謐。在這無人之境,水波總是循規蹈矩的,石頭的稜角屢遭挫磨,就連遠洋貨櫃船隊也收拾得整齊劃一。冷不防,金色的浮雲、怪鳥與半圓不明物體毫不識相的闖入畫面,以笨拙的造型與大刺刺的姿態打亂了洞窟世界的秩序。顯然,藝術家的筆墨總結了生活經驗,更以奇想細訴城巿的夢與渴望。我們的夢與渴望如何築構城巿的面貌﹖又如何想像出不一樣的城巿﹖

To convey the artist’s experience of urban life, the composition and arrangement of her works evoke the mechanical logic of modern architecture while the giant ship, forests, rocks and mountains are depicted with delicacy and tenderness. Like treasures cupped in one’s palm, both the natural scenery and man-made infrastructure are portrayed with soft, distinct brushstrokes and light, agile outlines, as if to wash the dust off our souls with ink art. In this uninhabited terrain, water flows obediently in regular patterns; the sharp edges of the rocks are filed down; even the ocean-bound container ships are laid out neatly. Without warning, golden clouds, strange birds and an unknown semi-circle object intrude into our field of vision, disrupting the order of the cave with their clumsy appearance. Evidently, the artist pays attention to conclude her experience of life with her refined brushwork, and even more so to speculate on her dreams and desires for a city with her whimsical compositions. How do our dreams and desires create the appearance of a city, and how do we imagine a different city?

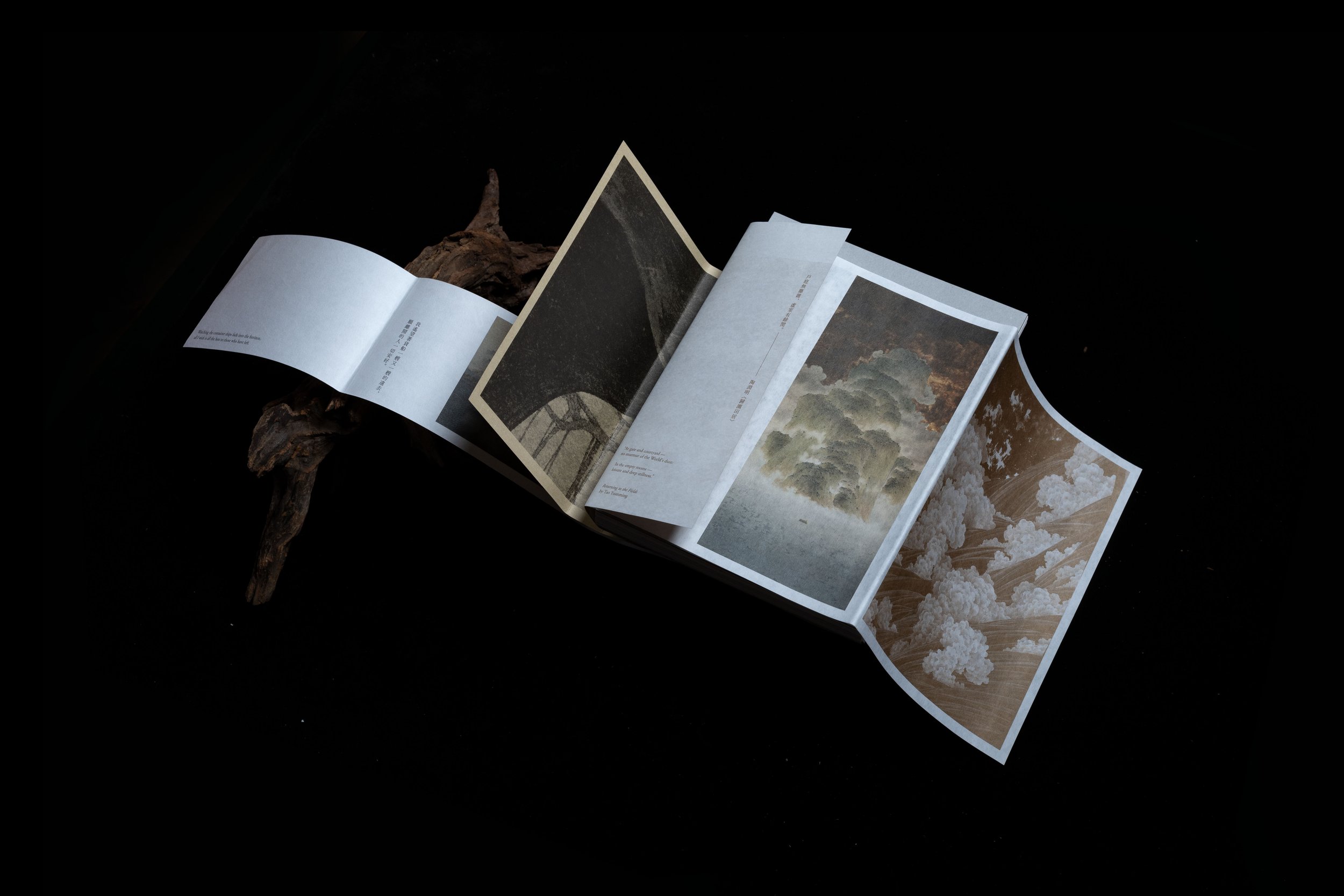

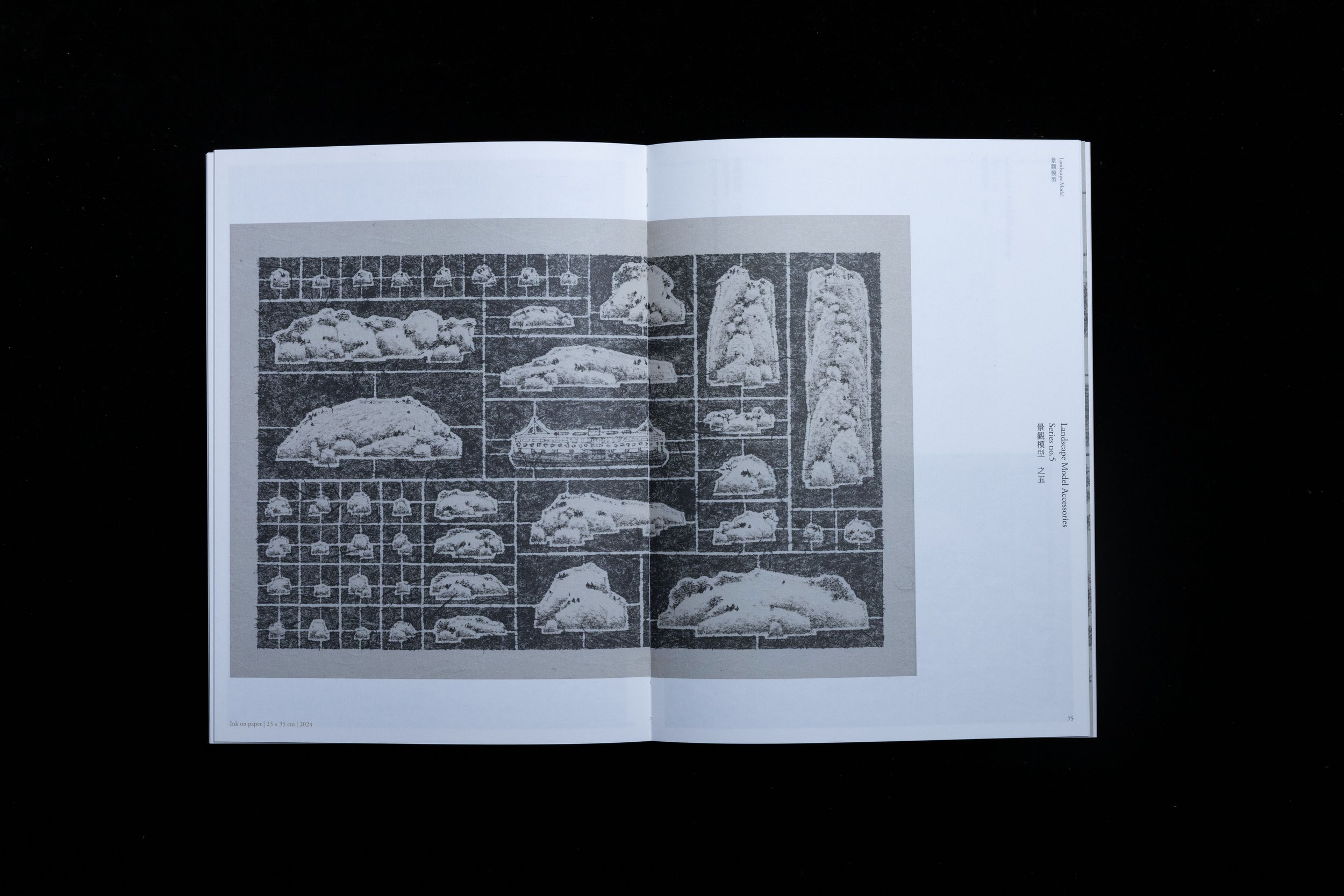

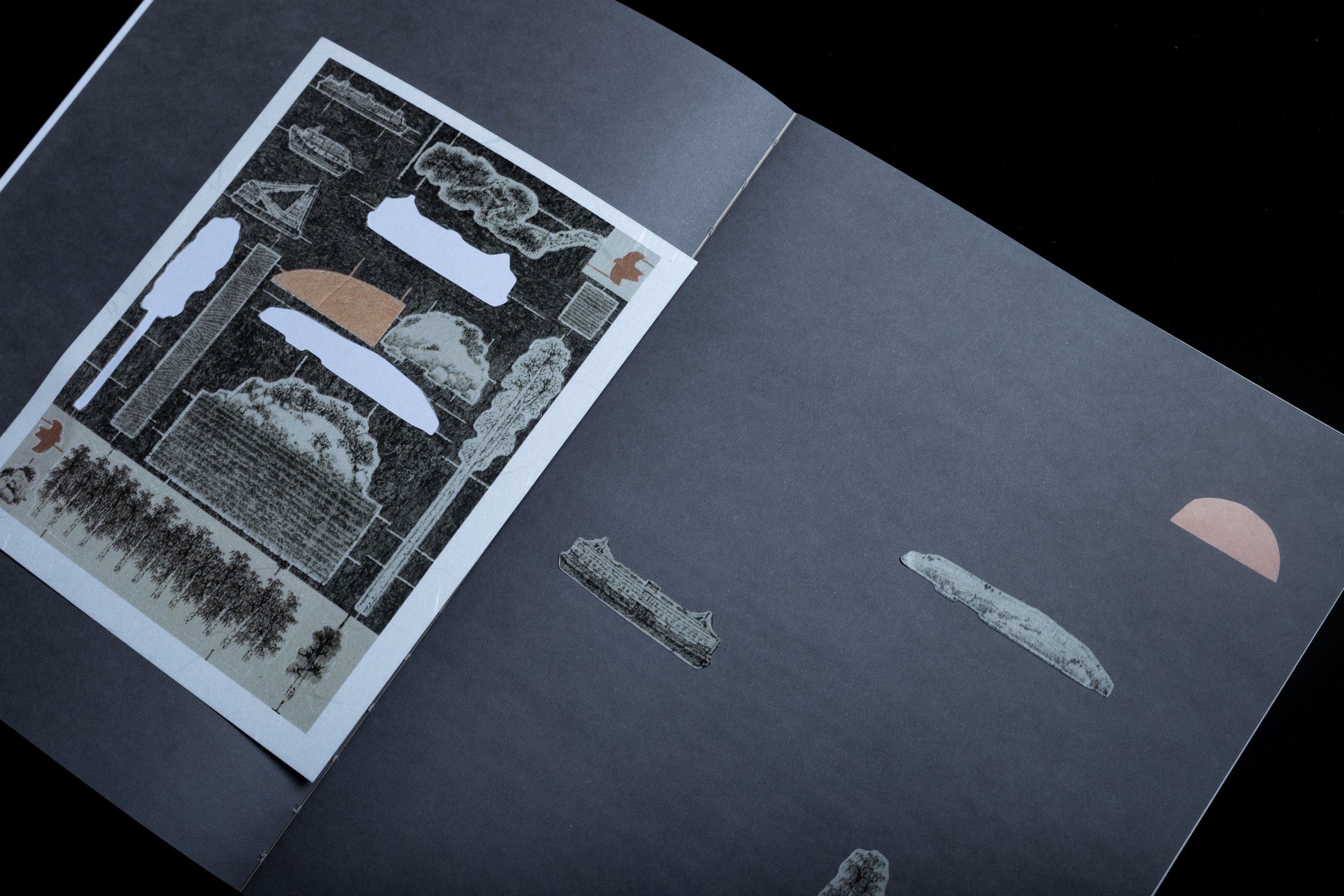

夢是無邊無際、流動又捉不住的。在〈景觀模型〉系列,藝術家將畫紙看成是模板,把洞窟世界的想像拆解成任意拼合的景物零件。山石路還原為一粒粒石子,海水田切割成水波片箋。林木解散了,剩下一株株大小不一的雜樹零丁落索的。抽離於原來的洞窟想像,風景零件頓時無所安身。為什麼火焰似的金光鳥幾乎向著單一方向飛﹖牠們飛往何處﹖為什麼吊臂船、貨輪、魚艇與帆船都得並列一起﹖為什麼一座座山丘看來互不統屬,怎麼也湊不成重巒疊嶂的景貌﹖化整為零,藝術家瓦解其想象世界,也戳破眼前所見的虛妄。有機的自然景貌早已異變為人工合成裝置。洞窟原來沒有什麼好風光。

Dreams are boundless, incessant, unstoppable. In the series Landscape Model Accessories, the artist treats the paper as display stands, deconstructing and rebuilding the caves as if they were model kits. The mountains and roads are reduced to stones, and the sea is broken down into fragmented waves. The forests have been disintegrated, leaving behind a scattering of differently sized trees, alone or in small groups. Detached from the imaginary caves, the model parts are deprived of a place in the painting. Why do almost all the fiery golden birds head towards the same direction, and where are they flying? Why are the crane barges, container ships, fishing junks and sailing boats juxtaposed with each other? Why do the hills look disconnected from one another, rather than integrated into the same landscape? With these fragments, the artist rips apart the world of her imagination and exposes the transience of our gaze. The organic, natural landscape has been replaced by man-made devices. In the end, there is nothing scenic about the inside of the cave.

然而,藝術家卻將散落的風景零件以紙板模型的方式排列,卻故意略去洞窟的背景構件,倒似邀請觀眾建構屬於自己的理想風光,並且自行填補想像空間的缺漏。風景零件毋寧是沈君怡創作的一套水墨山水符碼,以一石一木重構理想世界的無限可能。究竟符碼何所指﹖這有待觀眾在想像建構的過程,重新思考其對世界的認知、對美好生活的渴望,由此而賦予理想景觀的內涵。藝術家以一筆一劃模擬機械生產的模板,將背景渲染得暗沉,突顯景觀零件用筆的通透輕盈。虛實輕重的比照下,意義不明的山水符碼彷彿呼喚人走入建構理想境地的夢。一個個符碼亦因而逸出藝術家私密的想像世界,轉化為人人得以支取的夢的材料。從旁觀者化身為築夢人,我們想看到什麼樣的風光﹖

Even as the artist depicts the scenery in the form of model assembly kits, she deliberately skips the components of the cave’s background, as though inviting the viewer to close the gaps in their imagination by conjuring their own ideal scenery. Sim Shum has created her own set of symbols of ink landscapes with these scenic elements, rocks and trees to explore the possibility of constructing an ideal world. To what exactly do the symbols refer? To answer this question, the viewer must reconsider their understanding of the world and their worldly desires while conjuring the imaginary scenery, thereby conferring meaning on an idealised landscape. As the artist imitates the machine-made model kits in her paintings, she enhances the lightness and translucency of her brushstrokes against backgrounds in dark washes. Marshalling the visual impact of contrasts between solid and void, light and heavy, these landscape codes of unknown significance lure people into the dream of creating an ideal realm. These codes and symbols are thus released from the artist’s private world of imagination and become accessible materials to everyone to construct. What scenery do we want to see when we transform from a bystander to a dream builder?

藝術行動﹕觀看與築夢 The act of art making: seeing and building dreams

沈君怡筆下,山水不再是道教神仙的居所,一石一木也無法體現宇宙萬象變化之道。回應當代視覺文化,她的洞窟系列將山水林木鑲嵌於幾何面塊,觸動觀眾檢視畫面構圖的邏輯,反思自己看畫看世界的方式。我們究竟看什麼﹖如何看﹖又如何破解觀看的盲點﹖

Under Sim Shum’s paintbrush, the mountains and sea are not where the Taoist immortals reside, and the rocks and trees are not reflective of the systematic, transformative way in which this cosmos comes to be presented. With the landscape elements embedded in geometric planes, her cave series is a response to a contemporary visual culture, prompting the viewer to examine the logic of the composition and reflect on their perception of seeing art and the world. What are we seeing? How do we see them? How do we tackle the blind spot in our vision?

藝術家將想像的洞窟世界帶給我們,又以景觀零件系列解構山光水色,暗示眼前所見的虛妄—不論想像的、現實的,世間好風光不免煙消雲散。即使什麼也留不住,畫作卻召喚出具體行動,邀請觀眾以看得見的風景零件與看不見的想像,築構自己的理想境地。

Sim Shum brings to us her imaginary world of caves and deconstructs the scenic landscape into model parts, hinting at the inevitable transience of things in front of us — beautiful scenery, both imaginary and real, will eventually disappear. Even though nothing can we take hold of, the real action of her paintings seems to ask the viewer to create an idealised realm with the visible model parts and the invisible power of imagination.

千百年來,我們想像洞窟埋藏著久被遺忘的秘密、期待不為人知的寶藏終於破土而出。沈君怡的窟穴想像藏著的,不是看得見的秘密,而是建構想像過程中,看不見的渴望與夢想。可幸的是,藝術家以其創作總結此時此刻的生活經驗,也將看得見的圖像轉譯成觀眾築構自己的夢的符碼。

For over thousands of years, people have dreamed about caves that hide the longtime forgotten secrets and looked forward to the eventual discovery of unknown treasures. Instead of the visible secrets, the artist’s imaginary caves store up invisible desires and dreams. With her creation, she summarises her life experiences of the moments and translates the visible images into the symbols with which the viewer builds their own dreams.

或許繪畫召喚的,是觀眾的承諾。記著我們的渴望與夢想,莫失莫忘。

Perhaps what her paintings elicit is a promise from the viewer: hold on to our desires and dreams, and never lose or forget them.

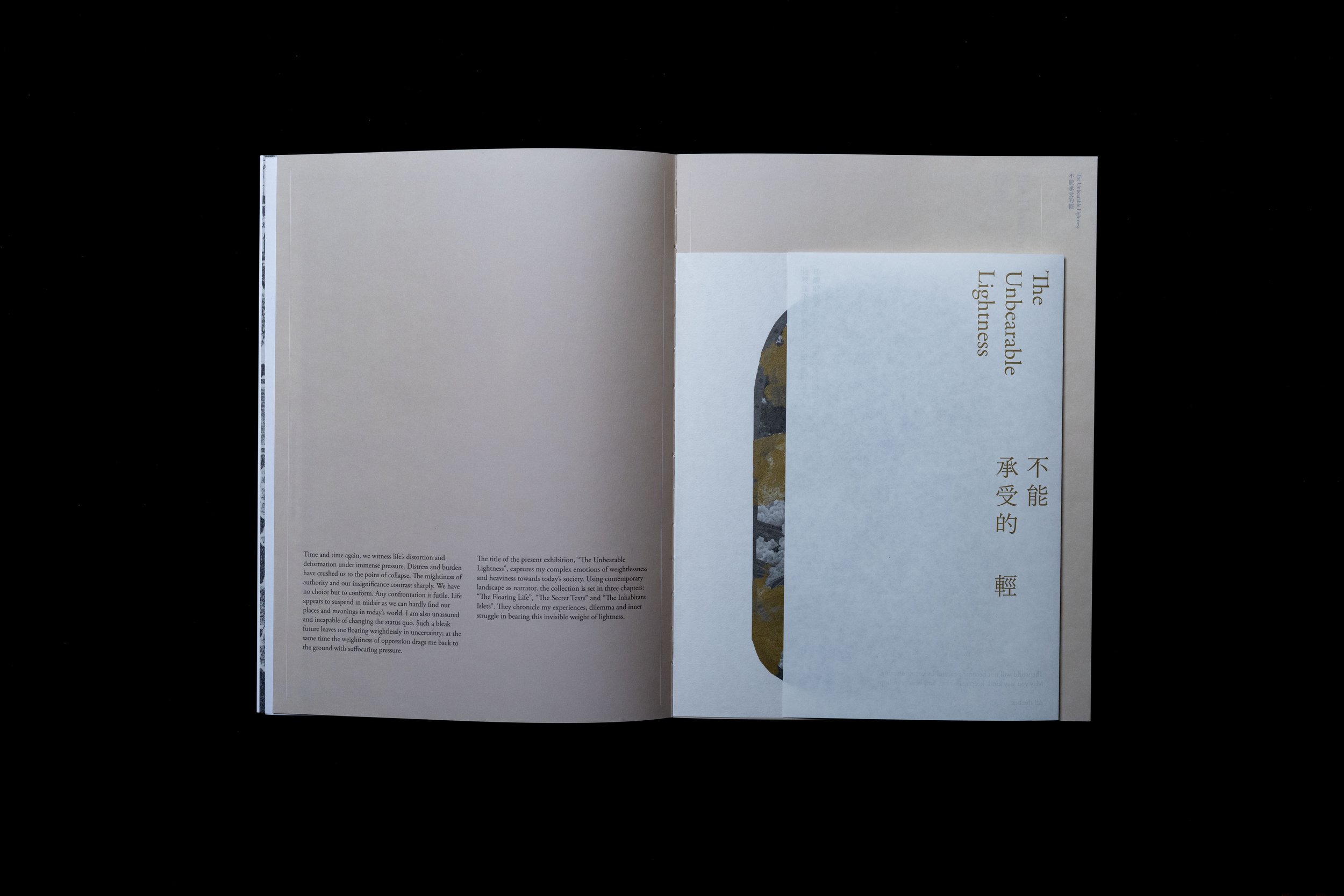

紅藥丸還是藍藥丸-沈君怡新作

Red Pills or Blue Pills – Reflections on Shum Kwan-yi’s new collection

歐陽憲 Henry Au-yeung

沈君怡的新展覽「⽯窟遊樂園」 是建立在⼀個巨⼤的譏諷上。 觀者或媒體都試著解開謎團。仔細觀看後,我才知道這個秘密(細看才知箇中妙趣),並能享受藝術家精⼼巧妙的策展。

The basis of Shum Kwan-yi's latest exhibition "Landscape of Haven," is a hidden irony that neither visitors nor media coverage has been willing to divulge. Before I viewed the collection and had a chance to appreciate the small astonishment and details that the artist had so thoughtfully sown, I was unaware of the secret.

藝術家把畫廊的入⼝設計成⽯窟的拱形,進內觀眾⾒到沈⽒畫中主⾓構建拼圖(拼砌)的細緻環境:她沒意識到⾃⼰⼀⽣都在洞⽳中過活。對,她是活在⼀個不太可能(難以相信)的理想世界中,呈現整潔,有序(井然有序)且精⼼計劃的結構。 ⼯整的樹⽊和岩⽯排成⼀列,所有構圖都

蘊含著強烈的處⽅感(制式化的構圖?)。試問⼤⾃然如何(豈能)如此不⾃然? 沈君怡解讀他們為敦煌⽯窟,我反問也許是柏拉圖的洞⽳!

Entering the gallery, viewers can see how painstakingly Shum has pieced together a story around her protagonist, who is unaware that she has spent her whole life in a cave. Yes, she does live in an implausibly perfect world with a clean, well-organized framework. There is a strong feeling of prescription ingrained in all perceiving intuition, and trees and rocks are aligning with architectural precision. How could nature be so deliberately artificial as to be so unnatural? Shum mentions Dunhuang's caves. I believe they belong to Plato!

現實及其對個⼈感知和⼼理的重要性是哲學辯論之⼀⼤重點。眾所周知,柏拉圖的洞⽳寓⾔是我們如何理解感知與現實,甚⾄⼤眾⼼理學的基礎。環境控制對個⼈現實的影響是深遠和相關的。這次展覽為我們提供了⼀個機會,比較柏拉圖的洞⽳理論和沈⽒的的⽯窟思為(思維/觀念)。

Realistic arguments about reality and its significance for personal perception and psychology are among the most heated philosophical ones. It is well recognized that Plato's Allegory of the Cave serves as the basis for our understanding of reality, perception, and even mass psychology. Environmental controls have dangerously relevant consequences on an individual's reality. This exhibition offers us a chance to look at the comparisons of Plato's construct in relation to Shum’s version of haven.

《洞⽳寓⾔》源於柏拉圖名著《理想國》,深入研究擴展現實和知識的觀念。它旨在展示觀點與信念,真實與虛幻之間的⼆分法。《洞》故事敘述未受過教育的囚犯如何被關在⼀個⼭洞中, 並且僅根據他們的知識了解現實。這是沈君怡展覽的出發點。展覽中她邀請觀眾選擇⾃⼰的感知道路:

挑戰正統認知(紅⾊藥丸)或保持⾃滿現狀(藍⾊藥丸)(⽤電影《廿⼆世紀殺⼈網絡》來比喻 )。

The Republic's The Allegory of the Cave was written to delve deeper into the concepts of knowledge and reality. It was intended to illustrate the contrast between belief and opinion, the actual and the imagined. The narrative describes how illiterate inmates were held shackled in a cave and could only understand their little knowledge of the outside world. This forms the basis of Shum Kwan-yi's latest exhibition, in which she asks viewers to choose their own route by either remaining complacent (blue pill) or advancing knowledge (red pill), using the Matrix analogy.

莫⾼窟的壁畫是沈君怡新作靈感來源。莫⾼窟位於中國⽢肅省絲綢之路的⼀⽚綠洲,是宗教和⽂化交流的⼗字路⼝(交匯處)。就像⽯窟畫⼀樣,沈⽒故意以線性基礎精⼼建造了她的構圖。畫中每個圖案都是精⼼ 「種植」的成果,以增強虛構的現實。當然,乍看之下,觀眾什麼都不知道(未有察覺異樣)。儘管更敏銳的觀眾會得到隱藏的信息:那就是我們不假思索地接受了⽣活中⼤多數的事情 ── 接受了世界原本的樣⼦﹗試問你上次思考⼀棵樹有多奇特是什麼時候?我們經常假設在電視、電腦或⼿機上看到的東⻄是真實的(所⾒的影像為實),從網路上看到或聽到的訊息視為理所當然(所聽的訊息為真)。

The murals of Mogao Caves, an oasis in Gansu province, China, at a crossroads of religion and culture along the Silk Road, served as the inspiration for Shum's most recent paintings. Like the grotto paintings, Shum meticulously composed her structure with deliberate linear foundation. Each motif is carefully “planted” to enhance the effect of fabricating reality. Undoubtedly, the spectator is unaware of anything else at first glance. Though more perceptive viewers will pick up on the subliminal message—that we accept most things in our life without giving them much thought—they accept the world as it is. When was the last time you gave thought to how peculiar a tree appears? We frequently assume that what we see on television, our computer, or our smartphone is real. We take information from the internet that we see or hear far too often for granted.

當我們在指定的通道中走過展覽時,我們受到控制,只能看到藝術家允許我們看到的東⻄。在這種情況下,投射到牆上的符號、影像和陰影就是我們認知的⼀切。這是我們對景觀的理解,也是我們最終的新現實。洞⽳內的景觀可以透過多種⽅式表現出來,從恐懼和不安全感到無法逃離的城市、城鎮或家庭。

The basis of this analogy is that as we walk through the exhibition in a designated passage, we are kept controlled and are only exposed to what the artist allows us to see. In this case, the images and shadows projected onto the walls are all that we know. This is our understanding of landscape and ultimately our new reality. This landscape inside the cave can be represented in many ways, from fear and insecurity to a city, town or a family one cannot escape from.

我很喜歡這個展覽,因為它表現着喜劇和⿊⾊諷刺的層次。有些⼈喜歡住在洞⽳裡,就如喜歡住在迪⼠尼樂園⼀樣兩者都提供⼀定程度的娛樂,並暫時緩解「現實」世界的壓⼒。但其基本(背後)理念使本展覽不僅只停留在娛樂層⾯。像沈⽒的上⼀個展覽「不能承受之輕」(2022)⼀樣,它聚焦於現代科技(在監視和控制的意義上)強加給⼈類的新問題和困境。

I enjoyed this exhibition on its levels of comedy and dark drama; some people would like the idea of living in a cave in the same way others like living in Disneyland – both offer a level of entertainment and temporary relief from the “real” world. But the underlying ideas made the exhibition more than just entertainment. Like Shum’s last exhibition "The Unbearable Lightness"(2022), it brings into focus new issues and dilemmas that technology (in the sense of surveillance and control) is forcing on humanity.

⼼理學上有⼀種說法:控制環境,你就控制了感知;控制了感知,你就控制了⼈。從我們⽣活經驗和教育所知,限制⼀個⼈的知識只會讓他們陷入錯誤的現實。以任何⽅式限制⼈們是類比囚禁和鎖鏈的價值所在。但是,當有⼈掙脫束縛,發現他們所學的都是錯的時,會發⽣什麼事?

There is a saying in psychology, control the environment and you control the perception, control the perception and you control the person. Individual perceptions are gained and fostered based on the experiences and education in our lives and limiting what a person knows is simply keeping them in a false reality. Keeping people limited by any means is where the analogical captivity and chains hold their value. But what happens when somebody breaks free and discovers that what they have been taught is all wrong?

我堅信好奇(探索)學習是釋放⾃由的關鍵。⽣命中最好的禮物就是吸收知識,跳脫框架思考,成為好奇的哲學家,最重要是採取前所未有的探索性⼒量(踏出⼤膽創新的⼀步)。有時我們會盲⽬地⾏走(摸⿊探路),並嘗試從洞⽳中走出⼀條未知的道路,利⽤(依靠)粗糙的牆壁作為希望的光。有時⼀個艱難的時刻可能是我們需要抓住的契機。我學會珍惜⾯前可⽤來掙脫束縛的⼯具。別⼈可會說,你怎麼能⽤⽑筆衝破(破開)⽔泥監獄?

I am a firm believer that inquisitive learning is the key to unlocking our freedoms. The best gift in life is to absorb knowledge, think outside the box, be a curious philosopher, and most importantly be given the strength to take unprecedented steps. At times we walk blindly, as well as attempt to walk an unknown path out of the cave, using the rough jagged surface of the wall as a beacon of hope. Sometimes a rough object or tough time can be the saving grace we need to grasp at that time. I learned to never underestimate the tools that we have in front of us that can be used to break free. One may say how can you break out of a concrete prison with an ink brush?